Montague John Durnsford - Great uncle in our lineage.

Killed at the landing at Gallipoli on 25th April 1915.

Also killed that day was his second cousin. Frederick William Mann, also in the 9th Infantry Battalion. Montague enlisted adding his step father's name.

This photo from official photographers does not look anything like the one that has always been etched in my mind - but having compared this photo with his uncle he must take after the Durnford line, Uncle Edward on the left father Montagu on the right.

Both were members of the 9th Battalion, enlisted in Queensland and remembered on the Lone Pine Memorial at Gallipoli. Both are listed on Panel 31. Both were around the same age, both worked in trades, one as a painter, one as a carpenter.One lived in Chindra, in the Tweed River area of New South Wales, the other lived at the time in Ipswich on the southern side of Brisbane.

The sad part is that they probably had no idea that they were related, how their lives were intertwined, and how in death they lay together, never to be found, and it has taken 100 years to be able to associate the two.

Frederick William MANN, 9th Infantry Battalion

Montague John Durnford PACEY, 9th Infantry Battalion

Montague John Durnsford was born 10th September 1890 in Nebo in North Queensland. He was the only son of Montague Hadley Isaacson Durnsford and Mary Mann.

Montague carried a well established family name, one that could be traced over centuries, and one which while being traditional, also had extensive links to the Military in England, and particularly to the Royal Engineers.

But like most young boys at that time, Montague's early life was on a property. His father was the station manager. Extremely proficient as a horseman, and unfortunately it was his favourite animal that caused his death. Young Montague was 7 years of age when his father died. His grandmother, Ellen Mann, also died from a fall from a horse, both extremely unlucky.

His mother left the station, and then opened a shop in Mackay. She and the children moved there, where he most probably went to school with his sisters.

But in tough times, Mary did what most other women in the same predicament did, she remarried.

This marriage may not have been the kind of one that she had with Montague's father. In 1909, Pacey did the most unforgivable act, he took to the family with a gun.

He threatened to shoot

Montague's young sister, Roma, and her mother, while the other children hid

under the neighbour's bed, and then he shot the neighbour in the face, and

unbelievably, he managed to evade jail time, and to be found guilty, reason , he was drunk.

Money was extremely tight, and eventually Monty then worked with his step father, as a painter.

But he found time to join the Light Horse, firstly with the 11th in Bowen then moving to the 14th. Light Horse Regiment.

He was a bugler. A rather important

role in the Battalion and usually charged with the responsibility for calling the men to battle.

He was a bugler. A rather important

role in the Battalion and usually charged with the responsibility for calling the men to battle.Only there was no need at this battle.

Buglers were soldiers allotted to Battalion and Company HQ whose job it was to sound the various calls throughout the day in camp and signal different units in the field. So yes, he would have carried his Bugle around with him in the course of his duties

All my life, Anzac Day was remembered as the day we paid tribute to Monty. He died at the landing at Gallipoli, so the story was told, and now some 60 odd years later, that story requires some reworking.

To have been in the first landing Monty had to have been in the Beagle, and landed at 4.30am in the dark. Scrambling up those high sand banks, loaded down with equipment, and his pack on this back, in the cold, and wet from wading through the water, rifle held high above his head, probably the bugle around his shoulders.

But he didn't.

439 Bugler Montague John Durnford PACEY, 'D' Co., 9th Battalion.

So he landed from the HMS Colne in the second wave.

Second Wave

C Co. 9th Bn landed from the destroyer HMS Beagle

D Co. 9th Bn landed from the destroyer HMS Colne

The timing of the landing was such that the first wave landed around dawn, the second wave was timed to land 20 minutes later.

Frederick was in H company, his company were spread around the other ships of the 10th 11th and then the 12th Battalion was kept in reserve.

The second wave of the 3rd Brigade covering force met heavy fire form the slopes wither side of Ari Burnu and many of the boats were under fire all the way into shore. In some cases all the rowers were hit and the bodies had to be pushed overboard so that others could take over. The battleships Triumph Majestic and Bacchanti were bombarding the Turks when the landings were made.

Robert Hamilton was in charge of the group, and from his story:

|

| Men of D Company getting ready to land |

They landed at Hell Spit at Little Anu Burnu near Shrapnell Gulley

Around 5 am, Hamilton and the men of C and D Company in the second wave landed just north of Hell’s Spit at the southern end of Anzac Cove.

The Ottomans, alerted by the first wave’s landing and still in possession of Plugge’s Plateau overlooking Anzac Cove, directed intense fire on the second wave, including deadly shrapnel fire.

Numerous casualties were suffered among those coming ashore. The first wave had been landed far to the north. The naval midshipman steered the flotilla even further north, parallel to Anzac Cove.

The water became too shallow for the tows; they bunched and the boats had to be released. The men rowed furiously, under fire, for the steep hills of Anzac Cove ahead. 9th Battalion was the first ashore and landed around Ari Burnu shortly before 4.30 am. Confronted by precipitous slopes, under fire and mixed up with other battalions, there was confusion. However, eager to escape the fire and mindful of orders to press inland, most men dropped their packs, fixed bayonets and charged up the hills.

By daylight, Plugge’s Plateau was in Anzac hands. There, those present were sorted into their battalions and directed to attack their original objectives. Men from the 9th accordingly occupied 400 Plateau, its capture necessary for them to progress onto Anderson’s Knoll on the third ridge.

Hamilton and D Company, after charging up little Ari Burnu, turned south down Shrapnel Gully and onto the top of McCay’s Hill. Fearful of a major counter-attack, the battalion commander, Colonel Sinclair-MacLaglan, ordered the men to dig in along a defensive line across the lip of 400 Plateau and along the ridge at the head of Monash Valley.

These positions would change little over the coming seven months of the campaign. However, this order impeded the reinforcement of units forward of this line and allowed time for the Ottomans to bring up reinforcements.

At 9 am, Sinclair-MacLaglan decided that the 9th should face the Ottomans on the landward edge of Plateau 400. They were ordered forward towards Lonesome Pine ridge.

The Ottomans met this advance with a hail of fire. Many of the 9th were killed but Hamilton survived. The survivors filled gaps in the firing line for other units on Plateau 400, repelling incessant Ottoman counter-attacks and suffering from intense shrapnel fire.

This increased as the day wore on, the battle swinging in the Ottomans’ favour as their reinforcements entered the battle. Casualties were great and movement was impossible. Troops dug in, lying prone.

They hung on until the evening. Reinforcements and slackening fire at dusk allowed some consolidation of the line.

However, casualties continued. Hamilton, in the firing line continually for over 18 hours, was shot by machine-gun fire in the left foot late in the evening.

The 9th were relieved over 27 and 28 April. A roll call on 30 April showed that they had suffered 515 casualties, about half the battalion.

North Beach seen from the sea, North of Anzac Cove and Arı Burnu, with Plugge's Plateau above the tents of the casualty clearing stations and field ambulance units.

North Beach seen from the sea, North of Anzac Cove and Arı Burnu, with Plugge's Plateau above the tents of the casualty clearing stations and field ambulance units.The Turks

A hero team and Yahya Çavuş 'tular here with exactly three Enemy divisions, ala vuruştular wholeheartedly that they desire the God was concerned, they got together tonight"Thought-provoking a photo (Translated )

A hero team and Yahya Çavuş 'tular here with exactly three Enemy divisions, ala vuruştular wholeheartedly that they desire the God was concerned, they got together tonight"Thought-provoking a photo (Translated )

Turkish reaction

Lieutenant-Colonel Mustafa Kemal (left), whose actions as commander of the Turkish 19th Division won him lasting fame.

They could not be sent to Ari Burnu as it was not marked on the Turkish maps. Colonel Halil Sami, commanding the 9th Division, also ordered the

division's machine-gun company and an artillery battery to move in

support of the 27th Infantry Regiment, followed soon after by an 77 mm artillery battery.

They could not be sent to Ari Burnu as it was not marked on the Turkish maps. Colonel Halil Sami, commanding the 9th Division, also ordered the

division's machine-gun company and an artillery battery to move in

support of the 27th Infantry Regiment, followed soon after by an 77 mm artillery battery.At 08:00 Lieutenant-Colonel Mustafa Kemal, commanding the 19th Division, was ordered to send a battalion to support them. Kemal instead decided to go himself with the 57th Infantry Regiment and an artillery battery towards Chunuk Bair, which he realised was the key point in the defence; whoever held those heights would dominate the battlefield.

By chance, the 57th Infantry were supposed to have been on an exercise that morning around Hill 971 and had been prepared since 05:30, waiting for orders. At 09:00 Sefik and his two battalions were approaching Kavak Tepe, and made contact with his 2nd Battalion that had conducted a fighting withdrawal, and an hour and a half later the regiment was deployed to stop the ANZACs advancing any further.

Around 10:00 Kemal arrived at Scrubby Knoll and steadied some retreating troops, pushing them back into a defensive position. As they arrived, the 57th Infantry Regiment were given their orders and prepared to counter-attack. Scrubby Knoll, known to the Turks as Kemalyeri (Kemal's Place), now became the site of the Turkish headquarters for the remainder of the campaign.

The capabilities of the gun

- Feldgranate 96: a 6.8 kilogram (15 lb) high-explosive shell filled with .19 kg (0.45 lbs) of TNT.

- FeldkanoneGeschoss 11: A 6.85 kilogram (15.1 lb) shell combining high explosive and shrapnel functions. It contained 294 10 gram lead bullets and .25 kilograms (0.55 lb) of TNT.

- A 6.8 kilogram (15 lb) pure shrapnel shell filled with 300 lead bullets.

- An anti-tank shell

- A smoke shell

- A star shell

- A gas shell

The

German Army used the 77-mm (3-inch) field gun and could fire high

explosives with a range of 11,250 yards. However they also possessed

more formidable examples of artillery in the form of howitzers that

could project heavy shells and create enormous craters. German artillery

used the 10.5 cm (4 inch) Feldhaubitze 98/09 during the Battle of the

Aisne, which could fire the Feldhaubitzgranate 98, a 15.8-kilogram high

explosive shell or the Feldhaubitzschrapnel 98, a 12.8-kilogram shrapnel

shell. German artillery also used the German 21-cm Langer Morser (long

mortar) with a calibre of 8.3 inches and range up to 11,000 yards. Its

barrel could be fired at a high angle of elevation, which meant that it

could be positioned behind hills and ridges and fire on the enemy

positions on the other side. The German howitzer designed for siege

warfare fired various types of shell during the Battle of the Aisne

including high explosive shrapnel, small, high velocity shells, known as

“whizz-bangs” or “Jack Johnsons”. The HE shell fired by German 21cm

howitzers emitted black smoke and would cause the most devastation. They

could blow a crater 20 feet wide and 10 feet deep. Such explosions

destroyed villages, levelled trees and vaporised men. - See more at:

http://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/index.php/updates/the-first-trenches-of-the-first-world-war/#sthash.3B961nwA.dpuf

The German Army used the 77-mm (3-inch) field

gun and could fire high explosives with a range of 11,250 yards. However they

also possessed more formidable examples of artillery in the form of howitzers

that could project heavy shells and create enormous craters. German artillery used the 10.5 cm (4 inch) Feldhaubitze 98/09 during the Battle of the Aisne, which could fire the Feldhaubitzgranate 98, a 15.8-kilogram high explosive shell or the Feldhaubitzschrapnel 98, a 12.8-kilogram shrapnel shell. German artillery also used the German 21-cm Langer Morser (long mortar) with a calibre of 8.3 inches and range up to 11,000 yards.

Its barrel could be fired at a high angle of elevation, which meant that it could be positioned behind hills and ridges and fire on the enemy positions on the other side. The German howitzer designed for siege warfare fired various types of shell during the Battle of the Aisne including high explosive shrapnel, small, high velocity shells, known as “whizz-bangs” or “Jack Johnsons”.

The HE shell fired by German 21cm howitzers emitted black smoke and would cause the most devastation. They could blow a crater 20 feet wide and 10 feet deep. Such explosions destroyed villages, levelled trees and vaporised men.

The stories of the landings are well documented and give an excellent timeline.

The 2nd Brigade landed between 05:30 and 07:00, and the reserve 1st Brigade landed between 09:00 and 12:00, already putting the timetable behind schedule. The 2nd Brigade, which was supposed to be heading for Baby 700 on the left, were instead sent to the right to counter a Turkish attack building up there. At 07:20 Bridges and his staff landed; finding no senior officers on the beach to brief them, they set out to locate the 3rd Brigade headquarters.

The 1st Brigade was on the opposite flank to the 3rd Brigade and already getting involved in battles of its own, when its commander, Colonel Percy Owen, received a request from Maclagen for reinforcements. Owen sent two companies from the 3rd Battalion and one from the 1st Battalion (Swannell's) to support the 3rd Brigade.

Soon after, Lalor's company had been forced back to The Nek and the Turks were threatening to recapture Russell's Top, and at 10:15 Maclagen reported to Bridges his doubts over being able to hold out. In response Bridges sent part of his reserve, two companies from the 2nd Battalion (Gordon's and Richardson's), to reinforce the 3rd Brigade.

By this time most of the 3rd Brigade men had been killed or wounded, and the line was held by the five depleted companies from the 1st Brigade. On the left, Gordon's company 2nd Battalion, with the 11th and 12th Battalion's survivors, charged five times and captured the summit of Baby 700, but were driven back by Turkish counter-attacks; Gordon was among the casualties.

For the second time Maclagen requested reinforcements for Baby 700, but the only reserves Bridges had available were two 2nd Battalion companies and the 4th Battalion. It was now 10:45 and the advance companies of the 1st New Zealand Brigade were disembarking, so it was decided they would go to Baby 700.

From the 9th Association

The battalion embarked for Gallipoli on the destroyers HMS Queen, Beagle and Colne and famously were the first shore at Gallipoli at 4:28am, 25th April, 1915. It is believed that the battalion’s 2IC (2nd in Command) MAJOR J C Robertson was the first person ashore having been in the leading boat yet other histories (and noted historian C E W Bean) mention Lieutenant Duncan Chapman as the first man ashore.

Another soldier, Lance Sergeant Joseph Stratford (1179) was also reported in newspaper at the time as being the first man ashore. A labourer with three years service in the New South Wales Lancers before enlisting in October 1914, Lance Sergeant Stratford left Australia for Egypt with the 1st Reinforcements in December 1914.

He landed on Gallipoli on 25th April 1915 and, according to his Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau file, was killed attacking a Turkish machine-gun position after landing. Newspaper reports attributed LSgt Stratford as the first man ashore on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, however the claim was later questioned by the official historian Charles Bean, who wrote that Lieutenant Duncan Chapman, later killed at Pozieres in 1916, was most probably the first man ashore. Aged 34 when he was killed, Lance Sergeant Stratford has no known grave.

At the time of the landing, a Battalion at full strength numbered around 1000 men and a Company numbered 250 men. Thus there were 4 Companies to a Battalion. The 4 Companies within each of the Battalions of the 1st AIF were alpha coded A,B,C, and D*. The covering force was to be landed in two waves. In the 1st wave, 1500 men were to be landed and 2500 men in the 2nd wave. The 2nd wave landed some 20 minutes after the 1st wave so for this discussion about the first men ashore at Anzac our concern is only with the men in the 1st wave.

**********************************************************************************

For reference this story is to be found at www.anzacsite.gov.au and excellent resource of the events.

Why did the Anzacs land at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915?

A brief description of the landing

An excerpt from Denis Winter's book,25 April 1915 - The Inevitable Tragedy,

University of Queensland Press, 1994.

The landing scheme was a simple one, in outline at least. The 3rd Brigade's 4000 men would land as a covering force to secure a beachhead for two Australasian divisions made up of six brigades. Those 4000 would go in two waves.

The first, consisting of 1500 men, were to start from three battleships – Queen, Prince of Wales and London – then be distributed between twelve tows, each made up of a steamboat, a cutter (30 men), a lifeboat (28 men) and either a launch (98 men) or a pinnace (60 men).

The remaining 2500, the second wave, were to land from seven destroyers shortly afterwards. Those destroyers would wait near the island of Imbros and join the battleships, one and a half miles (about 2 km) from the mainland, at 4.15 am.

The first wave was scheduled to land a few minutes earlier, and the destroyers would then sail in, full speed ahead, adding a number of lifeboats borrowed from transport vessels to the tows that had been used by the first wave. Once the whole 3rd Brigade was ashore, the rest of the 1st Division would arrive on transports, grouped in fours and coming in at regular intervals.

Such, at least, was the plan, and its first stage was negotiated without difficulty. Troops on the battleships were woken at 1 am, given a hot meal and a drink while the tows were being got ready, and by 1.30 am were ready for mustering into companies.

This operation was carried out with impressive efficiency: no one spoke; orders were given in whispers. The only sounds were shuffling boots and muttered curses as men slipped on the ladders leading down to the boats. But for many, the tension of that still night magnified the sounds.

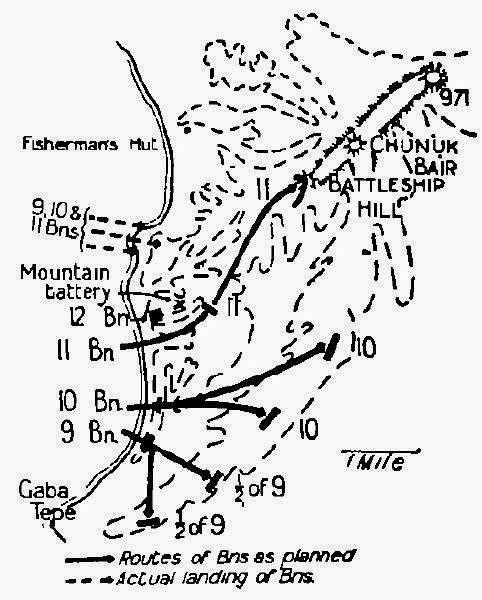

- War map of the landing at Anzac Cove including position of Turkish troops, first day objective and the actual ground gained.

"It was a still night," he recalled many years later. "There was hardly a breath of wind. Every sound seemed magnified tenfold and it seemed impossible that the noise of our boat hoists could escape being heard by the enemy a few miles away. We eagerly scanned the direction of the shore, the loom of which could just be seen, to see if we could detect any movement, but all was still."

The filling, which took about forty minutes, was supervised by adolescent midshipmen dressed in khaki-stained white duck and carrying revolvers almost as big as themselves. They checked the numbers and quietly called out, "Full up, sir!" at the right time. Naval officers then gave the order to "Cast off and drift astern" where the tows gathered, two on each side of a battleship.

The first wave was slowly gathered together in this way, enveloped by a sea mist which clung to the water like a shallow blanket. Orders required the men to keep greatcoats stowed in packs and wear tunics with sleeves rolled to the elbow so that flashes of white skin could give easier identification during the dawn assault.

Dressed so lightly, men were soon chilled to the bone; nor could they move to restore circulation. The little boats varied in length from just nine paces for the lifeboats to fourteen for the launches and what little space was left by the men was filled by two boxes of ammunition, twelve picks, eighteen shovels, a hundred sandbags, three jars of water, three days' rations and a quorum of wirecutters.

- The 10th Battalion in formation on the deck of HMS Prince of Wales, 24 April 1915. The battleship is leaving Mudros Harbour on its way to the Gallipoli landings. (AMW A01829)

The order to set off was given by Admiral Thursby using the Queen's wireless. Corporal James Bell (9th Battalion) later recalled the final stage. An officer on the battleship towering above his tow immediately called out, "Get away and land!"

There was an immediate tug on the painter and the tow moved off at a brisk six knots. On the battleship, sailors lined the side of the ship, giving the service's "silent cheer" by waving caps in a circle and "uttering a subdued whisper, barely audible to those on the boats".

How far offshore the battleships were by then remains uncertain. In his report of 8 May, Birdwood put the distance at four miles (about 6 km); Thursby's report agreed with the London's log on two miles; Callwell (Kitchener's Director of Operations) preferred one and a half; and the 1st Division's war diary recorded one. Whatever the actual distance, the journey took just forty minutes but with nerves wound up to such a pitch, few had any sense of time. To Cheney with the 10th, the journey seemed "like days", and to Lieutenant Aubrey Darnell with the 11th, "to go on for ever"; the last hundred yards were for George Mitchell "a lifetime".

As they closed on the peninsula, men whispered jests, and on the surface there was a sense of calm. "I am quite sure few of us realised that at last we were actually bound for our baptism of fire for it seemed as though we were just out on one of our night manoeuvres in Mudros harbour," Margetts was later to recall. But beneath the calm, all sensed an excitement that was tense and electric.

Set as they were on a flat surface without a shred of cover and incapable of evasive action, all knew that Turkish shrapnel – even a single machine gun – could scupper the first wave. All they could do was sit silent, still, frozen, and let silence and darkness magnify their fears. Mitchell tried to analyse his own feelings at the time but failed: "I think every emotion was mixed but with exhilaration predominant."

One 9th Battalion veteran later described how he had shivered and trembled uncontrollably throughout the journey, nervousness and excitement equally mixed. Blackburn, one of the scouts that day (and a future winner of the Victoria Cross), expressed it more simply: "The 30 or 45 minutes to the shore were the most trying of the lot."

What of the Turkish garrison meanwhile?

As the tows approached the cove, Lieutenant Colonel Sefik Aker of the Turkish 27th Regiment was looking out to sea from the Ari Burnu headland at the northern end of Anzac Cove. Later he described the scene:At 2 am the moon was still shining. The patrols on duty from my reserve platoon were Idris from Biga and Cennil from Gallipoli. They reported having sighted many enemy ships in the open sea. I got up and looked through my binoculars. I saw, straight in front of us but rather a long way off, a large number of ships the size of which could not be distinguished. It was not clear whether or not they were moving.

I reported immediately to the battalion commander, Major Izmet, first by telephone, then by written report. He said to me: "There is no cause for alarm. At most, the landing will be at Gaba Tepe" – and told me to continue watching these ships. I went to a new observation point and kept watching.

This time I saw them as a great mass which, I decided, seemed to be moving straight towards us. In the customary manner, I went to the phone to inform divisional headquarters. That was about 2.30 am I got through to the second in command, Lieutenant Nori, and told him of it.

He replied, "Hold the line. I will inform the Chief of Staff". He came back a little later and said, "How many of these ships are warships and how many transports?" I replied, "It is impossible to distinguish them in the dark but the quantity of ships is very large." With that the conversation closed.

A little while later, the moon sank below the horizon and the ships became invisible in the dark. The reserve platoon was alerted and ordered to stand by. I watched and waited.Australians were meanwhile peering anxiously in the direction of an unseen Colonel Aker. The night had been pitch black when the tows set off at 3.30 am, "so dark," wrote Bean, "that one tow could scarcely see a sign of the next one to it".

An occasional scatter of sparks from a steamboat's funnel or the dim phosphorescence in bow waves was the only sign that each tow wasn't alone. At 4 am, with landfall ten minutes away, the first glow of dawn allowed men to distinguish between hills and sky.

Bean spoke in 1919 of there having been "a brightening sky and a silken, lemon-coloured dawn breaking smooth grey behind the hills" when he briefed the artist Lambert on the monumental painting of the landing he was commissioned to produce, while Norris described the sea, in that first glow, as glistening "like a sheet of oil".

That same dawn allowed Colonel Aker and his men to see the tows clearly for the first time. In his words:

In a little while, the sound of gunfire broke out. I saw a machine gun firing from a small boat in front of Ari Burnu. Some of the shots were passing over us.

I immediately ordered the platoon to occupy the trenches on the high ridge which dominated Ari Burnu and sent only two sections under Sergeant Ahmed to the trenches on the central ridge overlooking the beach.

At the same time, I wrote a report to the battalion commander stating that the enemy was about to begin landing and I was going to a position on the far side with a reserve platoon. I ordered the withdrawal by telephone and set off immediately. On the way, we came under fire from the ships.Aker was severely wounded in the thigh during this action and his command passed to Muharrem, the senior sergeant.

It sounded like a sentry group. Then it began very fast. There was an exclamation, 'Hello! Now we're spotted.' It was a relief to hear the thing go. Here we are. Now we are in it." Loutit and Feint landed with the 10th Battalion on the tip of the Ari Burnu peninsula.

Just like the 9th, they came under fire about thirty yards out, although some of the battalion were more fortunate. Stanley's boat was fired on only when the noise of its keel grounding drew fire.

The 11th Battalion of the flotilla's northern flank landed along the northern face of Ari Burnu and had a hotter reception. Turkish firing began when they were about four hundred yards out – or so Darnell and Johnstone thought. Hedley Howe put it at two hundred and Everett at eight hundred. Tension obviously distorted the perception of men suddenly coming under heavy fire, but the fact remains that the 11th had the stiffest reception.

Opinion was less divided on how much firing there had been and where it had come from. Milne told Bean that the Turks were shooting "from the whole face of the hill" and Mills agreed with him, likening the effect to "a monster firework display".

After many interviews, Bean's despatch eventually stated: "The Turks in trenches facing the Landing had run but those on either flank and on the ridges above and in the gullies kept up fire on the boats coming inshore." Bean, however, didn't go along with men like Major Fortescue, who spoke of a solid mass of Turkish bullets and a cacophony of bugle calls.

- Odd memories from that first period under fire remained clear in some men's minds. Hedley Howe's is of a naval officer in the tow to his right shouting out, "Bear away more to the north. You're spoiling the whole bloody show." A few seconds later, a shower of sparks came from the funnel of that steamboat. "Then Abdul opened up with his machine guns."

Darnell remembered seeing a light on the tip of Ari Burnu: "It just flashed for a moment. Then we heard voices and what appeared to be a sentry. The call came from that point. The adjutant whispered to Captain Leane that they had seen us."

When the firing began, Darnell heard men singing snatches from "This little bit of the world belongs to us", while officers shouted, "Make a landing where you can, lads, and hold on!" They were using leather megaphones attached to their wrists because the sound of firing, reflected from the steep amphitheatre of Anzac Cove, was loud and seemed even louder against the hush of the previous silence.

Men's responses to being shot at for the first time varied, as described by Mitchell: "Some men crouch[ed] in the crowded boat while others sat up nonchalantly. Some laughed and joked while others cursed. I tried to scan the dim faces of our platoon and my section in particular. Fear was not at home."

One of Bean's anecdotes highlights the unexpected cheerfulness of men in a time of extremity: "The 11th Battalion had been told by someone that bullets would sound like birds flying overhead. The Turkish bullets, at short range, were anything but that, and one of the battalion's hard cases, Private 'Combo' Smith, set the whole boat laughing by remarking to his neighbour, 'Snowy' Howe 'Just like little birds, ain't they, Snow?'"

As for the cursing, Stanley thought it worth mentioning that "the language was awful". "Bloody", at this time, was the limit prescribed by custom for the majority of Australians, and Tom Louch endorsed this point when writing of Mena: "What really staggered us about the Tommies was their vocabulary. One four-letter word with variations provided nouns, verbs and adjectives – the staple of their conversation. The men in my section were not particularly straight-laced but they only swore in a mild way when exasperated." During those last minutes into Anzac Cove, the Australians were exasperated indeed.

- There were calm men too, and their example was priceless. Margetts told Bean: "A young midshipman in our cutter stood up. It did one the world of good to see him standing up. He had a great effect on our men. Four seamen had their heads well down in the boat and our men would have taken their cue from them."

Eric Bush described the quiet courage of a fellow midshipman:

Midshipman Longley-Cook was in charge of the Prince of Wales number five tow. "Go for'ard and get both bowmen up out of their forepeak and tell them to feel for the bottom with their boathooks," he told his coxswain Leading Seaman Albert Balsom, when the boats were nearing the shore.

Balsom had served with Captain Scott in the Antarctic and was a fabulously strong, brave man. "Why only one?" Longley-Cook asked a minute or two later. "I couldn't get the other able seaman up, sir. He's too frightened to move," Balsom replied. And while they were speaking, a rifle bullet entered the compartment and struck Balsom in the spine, killing him instantly.

A few minutes later, an Australian officer in one of the boats started to issue some orders, whereupon he was interrupted by Longley-Cook who, in a clear authoritative voice with a polished English accent (so I was told by an Australian who was there) said to the officer, "I beg your pardon, sir. I am in charge of this tow." The officer subsided into silence immediately and the troops in his boat were heard to mutter, "Good on yer, kid!".By this time most tows were about a hundred metres from the shore and the steamboats cast them off. "Those at the oars rowed like men possessed," Darnell told his father. "Some were shot and others took their place at once and not a word was uttered. Presently we grounded and, in an instant, were in the water up to our waists and wading ashore with bullets pinging all around us."

Private Gordon's landing was less accomplished. Responding to a sailor's exhortation to "Hop out and after 'em, lads", he promptly lost his footing on the slippery stones of the seabed, then fell a second time as he stepped ashore because of the weight of his saturated uniform. Meanwhile, Turkish bullets were killing and maiming in such a gratuitous manner that many men were deeply disconcerted.

Arthur Butler, the 9th Battalion's medical officer, recalled a calm midshipman handing him his satchel, "as if he were landing a pleasure party" when he fell back into the boat, shot through the head. Colonel Hawley, a Tasmanian, was shot through the spine and paralysed just as he was getting out of his boat.

The sea bed, though, seems to have posed the most pressing problem, as men leaving the boats got into difficulties. Bean put this down to the difference in size between small cutters which could get in close and large lifeboats which grounded in deep water but the facts are against him. The difference in draught between the biggest and smallest boats used was only a matter of 7 to 8 inches (18–20 cm).

As Salisbury put it to Bean: "Nobody was hit in our boat but some were drowned. Some jumped out up to their chests. Some to their feet only." Even where the depth was favourable, men could still have problems.

Boulders on the seabed could easily trip a man, while small pebbles and metal-shod army boots were a slippery match for top-heavy soldiers in full marching order – as Sergeant Douglas Baker found to his cost when he slipped and got a ducking. Nor were stones and boulders the only hazards. "Looking down at the bottom of the sea, Nicholas wrote later, "you could see a carpet of dead men who had been shot getting out of the boats". Private Eric Moorhead stepped on one of those bodies "in the wash of the water's edge" when he came ashore.

- The actual time of that first landing remains unclear. When he was briefing Lambert in 1919, Bean gave it at 4.53 am (but he had been well back on the transport Minnewaska and had had to rely on secondhand information).

Corps headquarters recorded 4.32 am as the time they heard the first rifle shots through the mist. Vice-Admiral De Robeck's report put it at 4.20 am. The 3rd Brigade's war diary and the report of the London agreed on 4.15 am. The 12th Battalion's war diary (they were reserve battalion to the first wave) states 4.10 am.

The early times best fit what we know of the destroyer flotilla's arrival but the matter is unlikely to be resolved. The circulation of synchronised watches, together with an appreciation of the need for absolute precision in battle planning only came in 1917. Before that clockwork watches recorded events with their usual approximation. When the corps timepiece stood at 4.32 am for example, the saloon clock on the Minnewaska read 4.28 am and Bean's own watch 4.23 am.

The exact location where the first wave waded ashore is rather more precisely established – but not entirely so. In the draft of his first volume and on most of his working maps, Bean put the 9th Battalion just south of Ari Burnu's tip and the 11th along about four hundred metres of beach on Ari Burnu's northern face, with the 1 0th on the tip. But ten years or so after the event Ray Leane, a stalwart of the 11th during the landing, begged to differ:

The boat I was in landed on the point. There were three boats to the left of us containing 9th Battalion men, most of whom were killed or wounded in the boat on the extreme left. If Commander Dix states that he was on the extreme right, he is wrong, because the l0th Battalion and one of the 11th were on the right of my boat.

I met Drake-Brockman after attacking and reaching the top of the point and he came up from the right side of the hill. The whole of the boats landed between the point and where afterwards the pier was built. My company was on the extreme left of the attack but the 9th Battalion boats landed to the left of us.

- Another view of Anzac Beach as it is today. Still in evidence are the steep cliffs that rise up immediately from the beach, which made ascent extremely difficult.

With such discrepancies still existing two generations after the event, a definitive resolution remains unlikely.The question of who was first ashore became another contentious issue soon after the landing. The Sydney Mail proposed Joseph Stratford, a New South Wales man who had enlisted in Queensland's 9th Battalion and died during the first day.

Lismore claimed the honour for its son and a school in Queensland was named after him. But Duncan Chapman, another 9th Battalion man, claimed priority in a letter dated 24 June 1915: "My boat was the first to land and, being in the bow, I was the first man to leap ashore." Bean supported Chapman and mentioned Frank Kemp, a sergeant scout, who corroborated the story. But since the tows landed on both sides of a peninsula with only the dimmest glimmer of dawn to illuminate the scene, it is difficult to discover a solid basis for any claim on this score.

One indisputable fact is that once the tows were well on their way to the shore, Thursby, in charge of the landing, shone a shaded light seawards and called in the destroyers. Major Alexander Steele recalled the engine-room bell of his destroyer clanging, then a 20-knot surge and an abrupt stop within the ship's length just two hundred yards (183 m) from the shore.

That surge of speed presented two problems: the lifeboats got into difficulties and the destroyers themselves became easy targets. Filled with men and breasting a steep bow wave, the lifeboats moved at a speed their designers had never contemplated, and in at least two cases ended in mishaps. The first involved Foxhound. A boat capsized and the senior NCO aboard was saved only by an airpocket that formed in his uniform.

Another man – Ernest Shepardson – seized a rope and was dragged along at high speed, submerged for the most part but drifting to the surface now and again. When the Foxhound finally came to a stop, Shepardson reappeared, "much to the surprise of his comrades who had thought him drowned a mile back".

The other incident, recounted by Richardson, had a more tragic outcome:

We were doing 18 knots. The man in the second boat didn't seem to be controlling his boat at all. She was slewing in and out for two minutes. A seaman called out that the pace was too fast but it didn't slow up. It couldn't. The boat then swung into the destroyer, slewed out and started to tip.

The water simply washed them all out of the stem except a man on the tiller who managed to catch the stern rope and began to crawl back along it into the boat. He [had] got one leg into the boat on the inside beam when she swung in again and crushed him. The men were all lined up, looking at it over the side. Half a dozen naval men put a rope round the poor chap, who was dying, and hauled him aboard.Corporal John Searcy was in the boat at the time. He tried to reach Private P.V. Smith, one of the drowning men, but was hindered by the weight of his pack. "I'm certain I heard his drowning screams," Searcy wrote many years later.

Meanwhile the destroyers had come under fire from Turkish snipers. The Beagle on the southern flank was particularly badly placed since it was within the range of Gaba Tepe's machine guns.

On the other flank, too, Turkish machine guns high on Walkers Ridge opened fire at almost point-blank range. Lieutenant Elmer Laing described those bullets hitting the side of the Usk "like hailstones on a tin roof".

Nor did all the bullets waste themselves on armour plating, as Captain Dixon Hearder, second in command on one of the destroyers, could attest:

I noticed a boy standing, more or less appalled at the din. So I walked up to him and said, "Come on, lad. No one is being hit." He pulled himself together and went on in front of me to the stern of the destroyer where there was a boat room. I followed right behind for another ten yards. I stepped aside to pass him and, just as I did so and got level with him, he just said "Oh!" and pitched forward on the deck. I did feel bad about him.Almost as unnerving as the sound of Turkish small-arms fire was the noise of the Royal Navy's covering fire. This began at 4.30 am. As Baker put it, "the noise was awful. I have never heard thunder equal to it."

The casual courage of many of the sailors was crucial in setting an example to the soldiers and helping the men through a difficult phase. Two incidents serve as examples.

As the boats were filling up, wrote Hearder, "talking was heard in one of them and one of the officers called from the deck, 'Who is in charge of that boat?' Great was the glee when a very dignified alto voice promptly replied, 'Naval officer in charge of this boat'.

The joke," Hearder added, "went on in the trenches. 'Make way for a naval officer', a private will squeak when he wants to get with water or something to the firing line." It was Hearder, too, who told of the incident, when a sudden burst of Turkish rifle and machine-gun fire halted disembarkation: "A cheery English voice on the bridge called out, 'Go on, lads. Get into the boats; these fellers can't shoot for tawfee.' " Hearder smiled to himself when he saw the Australians laughing at incongruity of the upper class English accent. "It was just the right note to strike," he concluded.

Unlike the first wave in the battleship tows, many of the destroyer men came under fire throughout the whole of the journey ashore, one man speaking of "shrapnel bullets striking the water with a noise like the popping of corks when drawn from champagne bottles". Private Edward Luders, a 1st Battalion signaller, saw a shrapnel shell kill sixteen men in a single boat.

- Photograph of the trenches at Quinn's Post later in the Gallipoli campaign.

The tows go in

By the time most of the 3rd Brigade's four thousand men had landed from the battleships and destroyers (at about 8 am), the main force in the transports had begun to arrive and the destroyers began ferrying them ashore, too. Private Robert Grant, who was aboard one of those transports with other 1st Battalion men, described his own experience graphically:Before dawn, I was asleep on the lower deck. When the ship's officer switched off the lights, the horses started to stampede in their stalls. This woke the troops who, in their semi-conscious state, groped about for their equipment which was lying loose at their sides.

Being pitch dark, they got in one anothers' way and this brought out some very impolite remarks. Eventually, they struck matches and, as day dawned, we began to take in the situation. I was near a porthole and put my head out. I could hear the crackling of rifles in the hills about a mile away.

The navy opened a terrific bombardment. Huge chunks of the Gaba Tepe fort flew about. The hills reverberated. Steam pinnaces towed laden boats of troops ashore, working with the regularity of the Sydney ferries. The destroyer Scourge came alongside. Her funnel was riddled with bullet holes and her decks were slippery with the blood of the wounded she brought to our ship. I watched them slung aboard. Never did I hate a ship more or want to leave it less than the Minnewaska.Bean was on the same vessel and was himself unnerved by the sight of the destroyer, her decks awash with blood.

A curious feature of that first morning was the speed with which conditions changed. By mid-morning, the Turks had been pushed back to the 3rd Ridge. The war had moved inland, and it was as if the gunfire from Ari Burnu and shrapnel from Gaba Tepe had never been.

"We were surprised how peaceful was our trip ashore," Colonel Dawson of the Auckland Regiment wrote. "A little shelling. Some dropping rifle fire but only two casualties in our battalion. The landing was peaceful but distinctly wet, particularly for us small ones. It is surprising what a lot of water a ship's boat draws.

The quietness of our narrow strip of beach was also surprising. A few Australians forming up; an Indian mountain battery and some wounded and dying men." And quiet it remained as the men trudged towards the first range of hills: "We advanced in the cool of the morning through thick undergrowth, heavy with dew and fragrant with the perfume of wild flowers," wrote Captain Andrew Came, 6th Battalion.

"Birds were singing in the bushes and the sun was bright overhead." With time to look around and take in the scenery, some men must have been surprised at the choice of landing place. Was a pebble beach less than the width of a cricket pitch a suitable site for landing the supplies for two divisions? Was a cliff of crumbling sandstone bush covered and carved up by deep gullies, really the best place to launch an offensive?

- Photograph of the reconstructed New Zealand trenchs at Chunuk Bair.

Was Anzac Cove the right place?

It was only shortly after the landing that high command let it be known that an error had been made – the landing should have been made on Brighton Beach, south of Anzac Cove and in a locality of relatively friendly topography.Instead and by accident, the men found themselves in the heart of precipitous country to the north of the intended landing area. Two explanations were proposed: a sea current had drifted the tows northwards and in the dim light of dawn the silhouette of Hell Spit or Ari Burnu had been mistaken for the intended aiming point, Gaba Tepe.

Both explanations can be safely rejected. If a stiff wind blew from the south-west, a set of one and a half knots flowed north-east. This fact was well known to the Mediterranean fleet, which had often visited Lemnos before the war, and was allowed for in orders issued to the marker ship Triumph: "It is absolutely essential for the success of the expedition that your ship should be accurately in this position [coordinates given].

Also record the direction of the tide and strength of the current and communicate both to Admiral Thursby after his arrival at the rendezvous." In the event, naval log books recorded a breeze blowing at just one knot during the landing, with the result, as Hamilton put it in his memoirs, that "Birdwood had no current to trouble him".

On the point of silhouettes, no one could possibly have mistaken the headlands in question. The high mountain of Sari Bair rises immediately behind Anzac Cove. The Khilid Bahr Plateau, on the other hand, is some distance behind Gaba Tepe and appears much lower from the sea, with a flatter top. If the tows had lost their direction during the period of darkness, there was time to make any necessary adjustments during the inshore journey because (so Bean told a correspondent) the outline of the land could be seen fifteen minutes before the tows set off.

The navigators accompanying the tows were certainly well qualified to make those adjustments. They had studied the shore's profile on a reconnaissance voyage just before the landing and would have made a particular effort to establish their bearings before moonset (2.57 am on the 25th). They would have had plenty of time to do so as well.

Thursby's report on the landing states that the loom of the land could be clearly seen at 2.30 am and, even one hour later, Colonel Johnstone found that he could "just see a faint outline of the coast." Godfrey went further. His memoirs state that he was "conscious of the loom of the land about 3 am", little more than an hour before the landing.

- Photograph of soldiers at Anzac, later in the campaign.

Put simply, Howe was saying that the tows were released at a point and in a direction exactly calculated. Since there was virtually no current on the morning of the 25th, any deviation in the tows' course requires explanation.

And there was a deviation – or, to be exact, two deviations, both noted by Major James Robertson of the 9th Battalion and others. "The naval people in the pinnaces seemed a bit hazy about the landing spot," Robertson wrote. "They stopped, changed course, and stopped again; and finally, when they were about two chains from the shore, a rifle shot rang out. This was the signal for full steam ahead and land as soon as possible.'' Metcalfe, then a midshipman, was more exact in the chart he sent to the War Memorial in 1973. "My effort was to show there was no error in navigation nor any current," he explained. On that chart he marked two places where the course had been changed, on each occasion by two points or 22.5 degrees.

The journal of Midshipman Dixon records the first change halfway in and Bean later confirmed his assessment when he briefed Lambert for his painting of the landing: "After fifteen minutes, the tows were sailing more or less in a line. They were swung to port by the naval officer in charge." Since the tows set off at 3.30 am and landed around 4.10 am, that change would have been made at 3.45 am, a little less than halfway in. The second change was made just before the tows landed.

According to Bush's midshipman's log, it was a shift of two points. Metcalfe judged that the change had been made two hundred yards from shore, while Leane of the 11th Battalion put it at three hundred yards, at the moment when the northernmost tow was Opposite Hell Spit. That was the change of course that sent the tows in a cluster towards the Ari Burnu peninsula, where they landed. The second would have been a visual one because the shore was close and dawn just breaking. But how had the first change been carried out in the dark?

Bean's working papers show him puzzling over the matter for years. The wording of the first reference in his draft, written in 1920, suggests his bewilderment: "The naval men appeared to see far more in the dark than the troops did, for as the land grew closer one after another picked up this movement and swung several hundred yards northward."

Three years later, Bean's address to cadets at Duntroon Military Academy, shows that his puzzlement remained. "Naval officers may have been able to see each other's tows but the soldiers could not for a long time." In other words, Bean had still been unable to discover how the first change of course had been made by all tows simultaneously. He was to go on puzzling into old-age, trying to explain why none of the soldiers had been able to tell him much when he interviewed them. Perhaps, he reasoned, "the overpowering strain of suspense (Was the coast defended? Had the Turks seen them?) [had] caused the raw soldiers in the boats to concentrate their thoughts and be less aware than the handful of British sailors who steered the tows".

*********************************************************************************

The actual landing of the troops was under the control of the naval authorities; the arrangements were worked out in detail, the naval orders for the Anzac landing occupying 27 typed foolscap sheets.

A concert was given, the items being contributed by members of the crew. At the close of the day a good hot meal, given by the ship, was supplied to all the troops, who were invited to eat as much as they liked, after which, for two or three hours, they were able to snatch some sleep.

About midnight the destroyers Beagle and Colne drew up alongside the Malda, and the men of "C" and "D" Companies dropped quietly over the side on to their decks. Two platoons of the 12th Battalion were also on each destroyer, beside which were seen the row-boats in which the troops were to land. For the next five hours the men could do nothing but sit or lie in their crowded quarters and talk or sleep. At 2 a.m. members of the crew came round with buckets of steaming hot cocoa, very welcome by this time, as the night was somewhat sharp.

The men in the Queen were awakened about midnight, and, after a drink of hot cocoa had been served out by some of the bluejackets, they began to climb down into the boats. It was then 1.30 a.m. on Sunday, April 25th, St. Mark's Day. "A" Company went into two tows on the starboard side of the ship, "B" Company into two on the port side. Each tow consisted of a cutter and two lifeboats. By 2.35 every man of the covering party from the three battleships was in his tow. Rear-Admiral Thursby, who was in command of the Anzac landing, with his flag in the Queen, says:

"The embarkation was carried out so quietly and expeditiously that I did not realize it had begun, and sent to know what was the cause of the delay. I would not have believed that the operation could have been carried out so quietly that I could not hear them, although on the bridge only a few yards away.

[As quoted by Admiral Wester Wemyss in "The Navy in the Dardanelles Campaign."]

The troops had not been able to see the coast from the ship, but they were able to see its outline faintly when they were in the tows. It had been a moonlight night, but the moon was now very low, and they had about an hour of absolute darkness ahead of them, as the first streak of dawn was due at five minutes past four, and sunrise at 5.15.

As soon as the men were in the tows, the battleships, which had been stopped since I a.m., began to move in slowly through a sea as smooth as glass. The tows advanced with them, each drawn by its picket-boat. About 3 o'clock the moon vanished. Half an hour later, the battleships having arrived as close to the shore as they could without running the risk of being seen, an officer on the bridge of the Queen called out in a clear, loud voice, "Go ahead and land." Thereupon the tows quickened their speed, and as they left, the sailors lining the sides of the Queen gave a "silent cheer" by waving their caps and uttering a subdued whisper, which was barely audible to those in the boats.

The naval officer in charge of the most southerly tow, one of those containing 9th Battalion men, was to give the direction, the other tows keeping in line with him at intervals of about 1.50 yards. It was now very dark, on account of a thick mist, and the men in the boats could hardly distinguish the tows on either side of them. Not a word was spoken above a whisper, and barely heard was the splash of the boats as the little waves lapped their sides. The suspense in the crowded boats was very trying: "I was shaking all over with nervousness and excitement," wrote one man.

Suddenly two searchlights, one after the other, shot their beams out ahead of the tows for a few moments. Fortunately they were on the far side of the peninsula, and so their rays could not reach the boats on account of the intervening hills. On reaching shallow water the steamboats cast off their tows, leaving the troops to row the remainder of the way to the shore. It was about this time that flames and sparks flared out of the funnel of one of the northern pinnaces to the height of at least three feet; this lasted for nearly half-a-minute. Shortly afterwards, at 4.29 a.m., there appeared on the top of a dimly-seen hill to the south a bright yellow light, which lasted for about half-a-minute. A single rifle-shot rang out from the shore, followed a second or two later by several shots. Then a heavier fire began.

At the sound of the firing the feeling of suspense ended. Some began singing in the boats. A voice was heard through a megaphone: "Make your landing, lads, where you can, and hold on." The boats almost immediately began to run aground, and the men, climbed over their sides and waded ashore as best they could. This was no easy matter, as the weighty equipment and arms impeded their movements, and underneath the water the bottom was slippery rounded shingle, not very easy to walk on with military boots. Some of the men found themselves in water half-way up their chests, but scrambling to the shore, they ran across a narrow stretch of beach until brought up by a sandy bank about ten feet high. Here they lay on the ground, took off their packs and laid them down, and fixed bayonets. Some had vainly attempted to fix their bayonets while in the water. Orders had been given that no shots were to be fired until daylight. [4 These orders were for the most part very carefully observed, despite the fact that a few men on first landing lost their heads in the excitement and began to fire into the darkness. It is said that of the men killed or wounded before daylight. none was found with a cartridge in his magazine and every one had the cut-off of his rifle closed, as instructed. This indicates the high state of discipline existing among the troops.]

Tradition has it that it was a 9th Battalion boat that was the first to ground at 4.30 a.m., and a number of its men had already reached the bank at the far side of the beach when the first shot was heard. To Lieutenant Duncan Chapman belongs the honour of having been the first Australian soldier to set foot on Anzac. He later reached the rank of major, and was killed in action at Pozieres in August, 1916. Among others in his boat were J. D. Bostock, F. C. Coe, E. Coles, W. A. Fisher, L. Hansen, T. A. Hellmuth, J. C. Henderson, C. Holdway, W. Jarrett, B. H. Kendrick, D. Kendrick, W. E. Latimer, R. McN. C. McKenzie, S. A. McKenzie, W. Pollock, B. Rider, and L. Thomas.

In the darkness it was difficult to see what was happening even close by. Many men were hit before they left the boats, some while in the water, and others as they were running across the beach. Some who had dropped into deep water were helpless on account of their heavy kits, and it is probable that not a few were drowned in this way.

At this stage it became apparent that some mistake must have been made in the point of landing. After forming up in the shelter of the bank, the orders were to attack the first ridge across the open ground. However, there was no open ground to be seen. The bank was the lower part of a high steep rugged hill. Some officers thought that this must be Gaba Tepe; others did not think so, but had no idea where they were. To add to the confusion the battalions were found to be mixed up. Men from the 10th were intermingled with those of the 9th.

It is now known that owing to a strong current the tows were carried out of their course, and made the shore at Ari Burnu, about a mile to the north of the intended landing-place. Some of the naval officers, realising they were off their course, had attempted to remedy the mistake at the last moment, and this it was that led to some mixing of the battalions. Major Salisbury, who was in 'the extreme right-hand tow, says:

"The naval officer guiding the tows [Lieutenant J. B. Waterlow] was in the picket boat of my tow. Apparently he was steering the right course for Gaba Tepe, for somewhat more than half way in to shore the rest of the tows had sagged away to the north and were out of sight. Some of the picket boats were smaller than the others and perhaps could not keep their loads up against the current setting north. Our tow was behind a large picket boat, and when the rest of the tows got out of sight to the north we turned north until we steamed across the sterns of the other tows with the naval officer apparently counting them; we then turned south to get back to our place on the right, but very soon the shore could be seen, so the picket boat drew up into position as third tow instead of first, thus sandwiching half of 'B' Company into 'A'."

Instead, therefore, of landing where there was a comparatively easy climb to the first ridge, the troops found themselves facing something which was in places very like a wall. In the meantime they were being met with rifle and machine-gun fire. One man states that, as soon as he reached the bank, he was "shot by a machine-gun through both knees, was spun round, and then fell down." Another, who could not find room at the foot of the bank, lay down a little further back, on the open beach, where he heard a succession of bullets passing just overhead, one of them hitting the man next to him.

However, it had been forcibly impressed on all that on landing they must advance at all costs, so as to clear the way for the main body. Consequently they began to climb the steep hill in front of them. On the southern side of Ari Burnu, where Major J. C. Robertson landed, was a steep bank as high as the wall of a room, and those attempting to climb it slipped back. Then someone found a rough track leading round it, and by this means they reached the top of the knoll.

Besides being very steep, the hillside was covered with scrub. This was mainly composed of small bushes of prickly dwarf oak, about three feet high, with leaves like a small holly: there was also a smaller arbutus, with leaves like those of a laurel. In places this scrub was so close and thorny that even a strong man had difficulty in forcing his way through it. A machine gun was firing from the top of Ari Burnu, but some of the men climbed up to it, quickly drove the Turks away from their gun, and captured a small stretch of trench from which it had been firing.

As they climbed the men cheered, swore, and joked; one of them afterwards said, "the swearing that went on, as well as the jokes, was marvellous." When they encountered any of the Turks they chased the enemy with shouts of "imshee yalla," "eggs-a-cook," "oranngees" (oranges), and other expressions which they had picked up in Egypt.

Some men of various battalions who had lost touch with their officers, cleaned their rifles and began shooting up at the flashes of the Turkish rifles far above on the hills. Captain Graham Butler, the M.O. of the 9th, who was attending to several wounded men on the beach, saw the uselessness of this, and realising that it might endanger the troops who had begun to climb the hills, urged these men to go on with the bayonet alone. He himself led them up a steep hill to Plugge's Plateau. How steep was the slope may be imagined by Dr. Bean's description in the Official History:-

"Those who were wounded (he says) rolled or slid down it until caught and supported by some tuft or scrub. Here and there a man hung over a slope so precipitous that Butler, going to his help, had to cut steps in the gravel face with his entrenching tool in order to reach him."

About 4 a.m. or a little later, "C" Company on the Beagle, and "D" on the Come, were ordered into the rowing-boats. A wooden staging had been fixed round the side of each ship, and the men stepped on to this and then down into the boats.

The boats from the seven destroyers were better distributed than those from the battleships, having a spread of over a mile from the northernmost to the southernmost, and they landed the battalions in correct order, although all were further to the north than had been planned.

When the destroyers reached a point about 500 yards from the shore, the commander of the Come shouted to the Beagle to move south, as they had steered too far north. However, it was too late to rectify the error. As the boats pushed off, the men in them could see the outline of mountains ahead, and the faintest streaks of dawn appeared. After leaving the destroyers the boats spread somewhat, with the result that the several parties of each company reached the shore at different spots.

But they landed under similar conditions to their comrades of "A” and "B" Companies, except that for most of them the slope up from the beach was not so steep. Part of "D" Company (Captain Jackson's) landed at Little Ari Burnu (afterwards known as "Queensland Point," or "Hell Spit") and part of "C" Company (Captain Milne's) about 300 yards further south, opposite the mouth of Victoria Gully. Others of "C" Company reached the shore a little farther south still, near the entrance to Clarke's Gully.

Colonel MacLagan, the brigade commander, was in one of "D" Company's boats, and as it approached the land, he looked through his night-glasses to see if the ridge immediately in front was occupied by the enemy. When the boats were about thirty yards from the shore they heard the first shot from in front of them, and then knew that the ridge was occupied; the Turks who were firing were under cover within sixty yards of the beach, some in trenches and some firing from the scrub.

The men landed, dumped their packs on the beach, and rushed the nearest of the enemy. Half-way to the top of the first hill (“M'Cay's Hill") part of Milne's company met a portion of Jackson's coming from the other side. This latter detachment, numbering perhaps half of the company, on landing at the side of Hell Spit, charged, cheering as they ran, over Little Ari Burnu and then began to move south. Going down the far side of the hill through scattered rifle-fire into a valley they found a small stone hut, in which were half-a-dozen Turks sitting by a fire with a pot of coffee on it. These Turks were bayoneted, and the company went on to the top of M'Cay's Hill, a few hundred yards further on, and there joined Milne's company. While some of "D" Company were crossing M'Cay's Hill. Sergeant T. A. Graham was shot in the thigh. "I'm done, boys, I'll never see Constantinople," he said, and soon afterwards he died, Lieutenant C. F. Ross wrote:

"I shall never forget the scene as we reached the top of the hills and could look back on the sea. Huge stabs of flame from the guns of a long line of warships reaching from Anzac to the Straits could be seen as they pelted shells at various points of the enemy positions.It was still too dark to see a man at 50 yards' distance. The staffs and troops of the main body on the transports could not gain much information of the progress of the landing. They saw the flare and heard the rifle-fire following it, and Some heard what appeared to be faint cheering-this would be either the shouting of the men in the boats during the actual landing, or else the cheering, swearing, and joking which went on during the charge up the hills.

As the light increased, the flame gave way to smoke, and the noise was terrific. Not only was there the noise of the firing of the guns and bursting of the shells, but the hills of the mainland seemed to take up the echoes and hurl them back to Imbros and Samothrace, whence they were re-echoed back again."

When daylight came, what was going on ashore could be discerned more clearly, especially by those who had telescopes or field-glasses. The men who were then landing, and those climbing the first ridge of hills, were visible and also the fighting going on along the sides and tops of those hills, but occurrences beyond the first ridge were for the most part out of sight of the ships. Enough of the fighting could be seen, however, to show the sailors and other onlookers what sort of men the Australians were. Admiral Wemyss was very much impressed, and to an Australian officer he afterwards said:

"Your men are not soldiers, they are fiends. I have seen many famous regiments charging, but I have never seen fighting like this. Your men will do me. It would give me great pleasure to lead them into action at any time."

Vice-Admiral de Robeck wrote:

"At Gaba Tepe the landing and dash of the Australian Brigade for the cliffs was magnificent-nothing could stop such men. The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps in this, their feat battle, set a standard as high as that of any army in history, and one of which their countrymen have every reason to be proud."

According to the original plan the troops after landing were to cross the ridge extending from Baby 700 to Bolton's Ridge, and to occupy the next one, Gun Ridge and its extensions. But owing to the mistake in landing too far north, another ridge was found between the beach and the one from Bolton's to Baby 700, with the result that the "first" ridge of the orders actually became the "second" ridge, and the so-called second" ridge the "third."' When daylight came the officers on Plugge's could recognise, from their previous study of the plans, the ridge which had now become the second ridge from a prominent feature on it, half-a-mile to their right front. This was a level-topped hill, a little higher than the rest of the ridge, which has been compared to a heart with its point to the sea. Known as the "400 Plateau," it should have been on the left centre of their landing-place.

At this moment, while the 10th Battalion should have been over the second ridge and on its way to the third, the 9th ought to have been far to the south hurrying to Gaba Tepe, which was two miles away from them when they expected it to be only 1000 yards distant. However, Major Salisbury led "A" and "B" Companies towards the 400 Plateau, moving thither across Shrapnel Gully a little to the south of the 10th, which had also left Plugge's, and was following retreating Turks. The seaward "point" of the 400 Plateau was not exactly a point but was separated into two spurs, the Razorback to the north and M'Cay's Hill to the south, with White's Gully between. Salisbury and his men climbed the steep Razorback, meeting only scattered fire, and reached the far side of the Plateau a little north of the head of Owen's Gully.

In the meantime, Lieutenant Thomas, with a platoon of Jackson's company, had reached the 400 Plateau and was reorganising in the scrub at its edge. One of his sections, under Corporal Harrison, was missing. The rest of the platoon then advanced across the plateau, its 50 men in a line about 300 yards from flank to flank. Reaching Owen's Gully-the valley which divides the northern lobe of the plateau ("Johnston's Jolly''.) from the southern one ("Lone Pine") - Thomas saw, about 200 yards ahead, some newly-turned mounds of earth which he thought were machine-gun emplacements. He saw, too, some Australians in the scrub to his right going straight in the direction of them.

Thomas tried to warn this party, but each time that his signaller stood up to semaphore the message, an enemy machinegun fired at him. Thomas then recognised the party. It was Harrison's section, which had reached the plateau some 300 yards south of him. Harrison had for a little while acted under the orders of Captain Milne, and then led his section across the plateau to join Thomas, whom he had seen (or had heard was) making towards Owen's Gully. Harrison, going to the northeast through the scrub, had just caught sight of a cup-shaped depression in front of him, when he came under machine-gun fire from the scrub beyond it. His men fell flat and crawled through the bushes to the edge of the depression, in which, immediately below them, they saw some tents. Other tents were visible further down the valley, while the smoke of camp fires was seen between them.

Harrison at once began to move towards these tents, and it was then that Thomas tried to signal to him. The only word that Harrison could make out was the last - "gun." But at that moment two field-guns fired close above his head. He called together his nine men and all crawled up the steep bank and found the guns just above them. There were seven Turks round the guns and fifty yards behind were others, loading machine guns on mules. They had not seen Harrison's party, and he told his men each to pick a member of the guns' crews, fire together, and rush the guns. All seven men round the guns fell.

A Turkish officer appeared at the entrance of the gun-pit and raised his revolver, but Harrison fired first, with the rifle from the hip, and the officer fell dead. The Australians next fired on the men who were loading the mules, and only one of them seems to have escaped. Then Thomas came up with his platoon and joined Harrison.

There were either two or three guns, and mules had already been harnessed to one of them. In a small roofed shelter was a quartermaster's store, containing books, papers, spare parts for machine-guns, leather equipment, tobacco and cigarettes. Some of our men wheeled one gun round to fire it on the Turks, but found that the breech-blocks had been thrown away. Bugler Maxwell, who was never seen again after that day, knocked off the sights; others, including some of the 10th who had by then come up, tried to burr the screws inside the breeches so as to put the guns out of action. These were the first guns captured at Anzac. [These guns did not remain in our possession, as they could not be removed at the time, and during the night they were secured by the enemy and withdrawn.]

Thomas now placed his men in a line in the scrub about 50 yards beyond the depression which Harrison had stumbled upon and which, for want of a better name, Dr. Bean has called "The Cup." As they were exhausted, they rested for ten minutes, and were allowed to smoke. The fighting hereabouts had temporarily ceased by this time, and there was no noise except a little occasional distant firing. A party of Turks with mules could be seen hurrying over the third ridge, that which was to have been the objective of the covering force.

Major Brand, the brigade-major, now arrived, accompanied by Lieutenant Boase and a platoon of Jackson's company. They crossed the plateau just south of Owen's Gully, passing on their way, near the head of the gully, a level patch of green grass and poppies, about 100 yards square, with the scrub forming a high border all round it. This was afterwards known as the "Daisy Patch." They passed by the south of The Cup without noticing it, and found Thomas's platoon lined out in the scrub.

The first definite orders for a change of plan were now given. The main parties of the 9th and 10th were arriving on the plateau, and the brigadier, Colonel MacLagan, followed them. He ordered that, instead of advancing to the third ridge, they should dig in and reorganise where they were, on the second ridge.

When Major Salisbury reached the plateau he collected the scattered men of the 9th who came up, and carried out the brigadier's instructions to dig in there. Leaving a platoon under Lieutenant Fortescue as an outpost lining the northern side of Owen's Gully, he set the others to dig in to the right of the 10th, making his line face to the south-east.

Captain Jackson, commanding "D" Company, having been hit on the way up from the beach to the 400 Plateau, Captain Dougall took command of the part of "D," which met men of "C" (as previously mentioned) on the way up to the plateau. Both parties reached the southern or Lone Pine end of the plateau. Victoria Gully on the seaward side, separated it from Bolton's Ridge, and where this ridge joined the plateau there was an enemy trench. Captain Milne was fired on from this position as soon as he arrived at the top of the hill, and was wounded. He sent a section under Corporal Harrison-the same who afterwards attacked the Turkish guns-to work round behind the trench, which was soon taken by this party and by the scouts, the few Turks in it being killed or captured. Milne moved into this trench; he was hit several times, and his second-in-command, Captain Fisher, had been wounded too, whereupon Milne left the trench, and went to the east till he reached the Turkish guns near The Cup.

Fortescue therefore went forward, to the south, and soon saw ahead some Australians who proved to be Costin and his machine-gunners. Costin knew nothing of the rest of the 9th, except that he believed that Haymen with a few men was in some gun position down the hill. Fortescue, who had now only seven men left, continued in that direction, and duly found Haymen with fifteen of his men in a somewhat sheltered position. Fortescue asked whether the firing-line was ahead, but Haymen replied that he was sure that there were no Australians in front of them, for he was being fired on from the front at short range.

Between 11 a.m. and noon, a battery of enemy mountain guns established near Scrubby Knoll opened a deadly fire on the 400 Plateau. The Turks were advancing on to Johnston's Jolly and to the bottom of Owen's Gully. Some of them even tried to steal across the gully into their old trenches on Lone fine, but they were stopped by fire from a party of the 12th on the northern side.

Salisbury had sent back for reinforcements, but as his messengers did not return and no reinforcements came, he consulted with Milne and they decided to retire to the summit of Lone Pine, about 300 yards in rear. Milne had already been wounded three times, and he now received two more wounds under circumstances which he himself described in a letter as follows:

"A man lying next to me got killed, and I put out my left hand to take his rifle and have a shot, and just as I did so a shell burst right overhead and hit me across the fingers, smashing the stock of the rifle to splinters, so I didn't have a shot that time. I got out my field dressing and tied them up and carried on, but very soon after a six-inch shell got to business and a piece of it ripped through the beck of my upper left arm."

http://alh-research.tripod.com/Light_Horse/index.blog/2007685/the-battle-of-anzac-cove-gallipoli-25-april-1915-9th-infantry-battalion-roll-of-honour/

Where did he get to?

Based on all the information, Monty in the second wave most probably made his way up the sandhills and then onto the area known as Schrapnel Gulley.But Monty's body was never found, nor was Frederick's. Why?

The story about Monty now gets quite confronting. Not nice, but what war or battle is?

Until 4 months ago, it was my belief that as we had been told, Monty died at the landing.

But there were niggly questions, especially as we had visited Anzac Cove and seen the sandhills, and the terrain, and the pebbly beach.

The war diaries of the 9th could not possibly reflect what happened on 25th April, and again questions. The answers were that the adjunct was supposed to keep the records, but that didn't happen. The diaries were written a few days later.