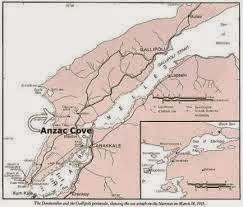

The Landing at Ari Burnu - Now known as Anzac Cove.

And so the story of Gallipoli began at two places, 15 kilometers apart.

April 1915

17 – British submarine E15 runs aground in the straits.

- 25 – British Empire and French forces make amphibious landings on the Gallipoli peninsula.

- Landing at Cape Helles made by the British 29th Division and elements of the Royal Naval Division.

- Landing at Anzac Cove made by the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC).

From Istanbul it is about a 5 hour drive.

It is on the Western side of the Turkish Coast, in an area known as the Dardenelles. On the west coast of the Peninsula. It fronts the Agean Sea.

The Dardanelles (/dɑrdəˈnɛlz/; Turkish: Çanakkale Boğazı, Greek: Δαρδανέλλια, Dardanellia), formerly known as Hellespont (/ˈhɛlɨspɒnt/; Greek: Ἑλλήσποντος, Hellespontos, literally "Sea of Helle"), is a narrow strait in northwestern Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara. It is one of the Turkish Straits, along with its counterpart, the Bosporus. It is located at approximately 40°13′N 26°26′E. The strait is 61 kilometres (38 mi) long but only 1.2 to 6 kilometres (0.75 to 3.73 mi) wide, averaging 55 metres (180 ft) deep with a maximum depth of 103 metres (338 ft). Water flows in both directions along the strait, from the Sea of Marmara to the Aegean via a surface current and in the opposite direction via an undercurrent.

Like the Bosporus, it separates Europe (the Gallipoli peninsula) from the mainland of Asia (Anatolia). The strait is an international waterway, and together with the Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus, the Dardanelles connects the Black Sea to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Çanakkale Suspension Bridge has been planned, connecting Sarıçay (a district of Çanakkale Province) on the Asian side to Kilitbahir on the European side. At this point, the strait is narrowest.

The Dardanelles were vital to the defence of Constantinople during the Byzantine period.

Marble plate with 6th century AD law regulating payment of customs in the Dardanelles

Also, the Dardanelles was an important source of income for the ruler of the region. At the Istanbul Archaeological Museum a marble plate contains a law by the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I (491–518 AD), that regulated fees for passage through the customs office of the Dardanelles (see image to the right). Translation:

... Whoever dares to violate these regulations shall no longer be regarded as a friend, and he shall be punished. Besides, the administrator of the Dardanelles must have the right to receive 50 golden Litrons, so that these rules, which we make out of piety, shall never ever be violated... ... The distinguished governor and major of the capital, who already has both hands full of things to do, has turned to our lofty piety in order to reorganize the entry and exit of all ships through the Dardanelles... ... Starting from our day and also in the future, anybody who wants to pass through the Dardanelles must pay the following:

– All wine merchants who bring wine to the capital (Constantinopolis), except Cilicians, have to pay the Dardanelles officials 6 follis and 2 sextarius of wine.

– In the same manner, all merchants of olive-oil, vegetables and lard must pay the Dardanelles officials 6 follis. Cilician sea-merchants have to pay 3 follis and in addition to that, 1 keration (12 follis) to enter, and 2 keration to exit.

– All wheat merchants have to pay the officials 3 follis per modius, and a further sum of 3 follis when leaving.

Since the 14th century the Dardanelles have almost continuously been controlled by the Turks.

*********************************************************************************

During Gallipoli campaign the island of Lemos, part of Greece, shown in the map, played a huge role.

The different battle Zones of the Peninsula and noted on the map on the right, are Suvla to the top left hand side, followed down by the coast to Anzac, the the right around the narrowist part of the straits is Helle, and then on the bottom, is known as the Dardenelles.

The driving distance from Istanbul to the Gallipoli peninsula is about 5 to 6 hours.

There is a ferry service from the town of Cannakale, on the main land mass.

|

| Looking back to the Gallipoli peninsula |

Four areas, four zones, and all that is left now is for those who lie beneath the sands, never found, or never identified. They are remembered in all the cemeteries below.

|

| Anzac Cove towards Suvla |

|

| To the south of Anzac Cove |

|

| Anzac Cove |

|

| Helles |

|

| Dardenelles |

On 25th April 2015, at 4.30am in the morning, just as the sun rises, where 100 years ago, a flotilla of landing boats made there was towards the shore. They had been moored in the waters off the beach. Not a sound was to be made.

Did they really think that they were unseen?

Suddenly a belch of sparks from one of the convoy. Lights shone towards the beaches, illuminating the waters. Guns roared, men fell over dead before they even made the beaches.

Unprepared, bayonets fixed, no shots to be fired. Doubled over with equipment, and their supplies, many just drowned under the weight of their packs.

Mistakes were made, sailors were shot, mere boys took over the task of getting the lighters onto the shore. Then a mad scramble for cover. Where? Huge cliff faces to the front. Confusion, noise, gunfire, was this how the story was really to begin? It ended before it began. Men simply disappeared, the lighter it became the more they were nothing more than targets for shooting practice.

Then 7.00 am and the big guns, mortar shells bombarded the landing craft, the beaches, men were obliterated, vapourised by the smoking guns. Why? Lessons of past Battles were not followed. Once more so many died, because of mistakes made by those who were supposed to protect them.

Once more it didn't seem to matter how many suffered, to gain an inch, and again, the generals were ducking for cover.

|

| Church before landing |

***********************************************************************************

25 April 1915 The landing

In the dark before dawn, battleships, destroyers and troopships

approached the Turkish coast where the Australians and New Zealanders

were to land.

In the dark before dawn, battleships, destroyers and troopships

approached the Turkish coast where the Australians and New Zealanders

were to land.The 3rd Australian Brigade (4,000 men) was to be the covering force, with other brigades to come ashore throughout that day and the next.

|

| 6th and 7th Battalions, 2nd Infantry Brigade, being towed by a steam-pinnace to Fisherman's Hut, North Beach, Gallipoli Peninsula. |

|

| First ashore |

|

Once off the beach the men faced high hills, cliffs and ravines. The terrain was not what they had been told to expect, but it provided some protection. Enemy fire began as soon as the first men came ashore.

Directed by sailors from a destroyer, a line is secured to help troops disembark on the beach. Behind them the cruiser HMS Bacchante has moved close to shore to provide supporting fire.

Scrambling up the hills, the Australians took the first ridges, but their objectives were still far off. The fighting in the hills and scrub became fierce, and this is where most of the day's casualties occurred. As the day went on, it became evident the task was impossible. Evacuation was ruled out, so the men were told to consolidate. The order came: "There is nothing for it but to dig yourselves right in and stick it out." The grand plan had failed, and months of further fighting followed for little gain.

|

| Watching the landing |

By 8 am 8,000 men, including the main force, were ashore. At the end of the day there was twice that number. The beaches were never the bloodbath that some writers and artists have depicted. Most casualties occurred during the fighting in the hills above the beaches, with the Turks determined to prevent the capture of the high ground.

By the afternoon of the first day the beach was secure, a wireless

mast had been set up and a pier built. Anzac Cove had already begun to

develop as the base area and the lifeline to the outside world that it

would become for the rest of the campaign. But a crisis had developed

with the casualties as the area became crowded with hundreds of wounded

and dying men desperately needing to be evacuated.

By the afternoon of the first day the beach was secure, a wireless

mast had been set up and a pier built. Anzac Cove had already begun to

develop as the base area and the lifeline to the outside world that it

would become for the rest of the campaign. But a crisis had developed

with the casualties as the area became crowded with hundreds of wounded

and dying men desperately needing to be evacuated.

Infantry landing at Anzac Cove

The casualties in the boats and on the beach were moderate. It was chiefly the endeavour to reach … the "Third" ridge, and the Homeric struggle that followed to hold the position achieved, that gave Australia "ANZAC Day".

It was early evening before boats

became available; many of the maimed and bleeding were sent off in

filthy barges.

It was early evening before boats

became available; many of the maimed and bleeding were sent off in

filthy barges.No one knows for sure how many Australians died on the first day, perhaps 650. Total casualties, including wounded, must have been about 2,000. This news trickled in to the Australian newspapers.

Even a month after the landing, only 350 deaths had been acknowledged.

Alex Gilpin had been fatally wounded in the stomach. All day he begged to be shot.

But despite all the horrors and the challenges of the situation, a camp was soon set up.

Reaching the beach, the first troops found they were almost two kilometres too far north. Also the boats had become mixed up. Traditionally, strong currents, or even a change in orders, were blamed, but it is likely that the task simply required more accurate navigation from those in the ships and their boats than was then possible in darkness.

Enemy resistance had also been underestimated. The Turkish defences

were only thinly manned, and even when reinforcements arrived they were

still out-numbered. Nevertheless, the terrain favoured the Turks: the

Anzacs were confronted by steep cliffs, ravines, and hills covered in

dense prickly bush. The enemy held the best ground, knew the area, and

were determined to defend it.

Enemy resistance had also been underestimated. The Turkish defences

were only thinly manned, and even when reinforcements arrived they were

still out-numbered. Nevertheless, the terrain favoured the Turks: the

Anzacs were confronted by steep cliffs, ravines, and hills covered in

dense prickly bush. The enemy held the best ground, knew the area, and

were determined to defend it. |

| The actual beach |

At last the day ended and I can tell you I have never spent nor wish to

spend such a long day again. The sights one saw will remain impressed on

my memory as long as I live.

Private John Gordon, 9th Battalion

On 25 April 1915, the Division, under the command of Ensign Donald İbradalı İbrahim, 9 27. Regiment 2. battalion 8. Squad 1. Fisherman's hut where the team against our troops went ashore after the ANZAC forces more no. 2 Outpost from an image at the Mule Gully station./The camp and surrounds of Mule Gully covered in snow

On 25 April 1915, the Division, under the command of Ensign Donald İbradalı İbrahim, 9 27. Regiment 2. battalion 8. Squad 1. Fisherman's hut where the team against our troops went ashore after the ANZAC forces more no. 2 Outpost from an image at the Mule Gully station./The camp and surrounds of Mule Gully covered in snow

Anzac Cove - The place where legends were made, boys became men, thousands of lives were lost,

|

Mates - Looking After Mates |

***********************************************************************************

The ANZAC Spirit

ORDINARY PEOPLE DOING EXTRAORDINARY THINGS

To cope with the tragic losses our country saw at Gallipoli, the men and women of Australia searched for the positive in the experience. To get through such a horrendous time the soldiers had to develop strong bonds with each other and demonstrate extraordinary courage, endurance and bravery.

So, today, when you hear someone speak about the ANZAC spirit, think of courage, bravery, endurance, mateship, determination and sacrifice. These are the values that were demonstrated so strongly by the soldiers at Gallipoli and are important in defining Australia as a nation.

Our First VC Winner

After the establishment of the Anzac line at Gallipoli in early May 1915, the Turkish commanders began making plans to force the Anzacs off the peninsula. New divisions were brought in and a great attack was scheduled for 19 May. In the words of Kiazim Pasha, Chief of Staff to the German commander of all Turkish forces on Gallipoli, Liman Von Sanders: ‘The plan was to attack before day-break, drive the Anzac troops from their trenches, and follow them down to the sea’.

As the Australians pulled back, Turkish soldiers occupied a few metres of the trench. The enemy, however, were unable to move up or down the trench because shots were being fired at them from connecting communication trenches. Some of these shots were coming from Lance-Corporal Albert Jacka who was occupying a fire-step in a firing bay. Two officers who ran into the trench, trying to get sight of or drive back the Turks, were both killed.

- Cover of sheet music, He was Only a Private – That's All

A new plan had Jacka taking a circuitous route through back trenches to get in behind the Turks. Once he was in position, another party would occupy the enemy with a bomb attack. As the bombs exploded, creating much noise and smoke, Jacka jumped out into no-man’s-land, ran to where the Turks were, and leapt in among them.

He quickly shot five men dead and bayoneted two more; the remainder fled. As Lieutenant Crabbe entered the position Jacka, his face ‘flushed with the tremendous excitement he had undergone during the previous hour’, greeted him saying, ‘Well, I managed to get the beggars, Sir!’ He was recommended for and received the Victoria Cross.

Albert Jacka's Biography

Jacka’s award was only the start of a military career that saw him become a ‘living legend’ within the AIF. Moreover, it was a reputation earned by his personal qualities of leadership in the only area really respected by front-line soldiers, that of the battlefield itself.

While Jacka could be outspoken and bloody-minded, attributes which many of his superiors saw as insubordination and which may had held back his promotion beyond his eventual rank of captain, everyone within the AIF came to know of Albert Jacka.

In France, he was twice awarded a Military Cross for actions that even that judicious evaluator of men, the official historian Charles Bean, felt should have earned him two bars to his Victoria Cross. At Pozières on the Somme in 1916, arguably the most terrible battle the AIF was ever involved in, Jacka’s presence of mind and courage virtually saved the day when a German counter-attack had broken through the line.

As forty Australian prisoners were being led by the triumphant Germans, Jacka, at the head of seven men, burst among them. Despite being hurled from his feet several times by explosions and wounded in the head and shoulder, Jacka killed nearly a score of Germans on his own and bayoneted others.

The 14th Battalion’s historian, N Wanliss, described this as a ‘brilliant counter-attack’ and Charles Bean was also lavish in his praise describing Jacka’s action as ‘the most dramatic and effective act of individual audacity in the history of the AIF’. From an official historian, who personally read over the stories of thousands of brave men that he included in his battle narratives, this was exceptional praise.

Albert Jacka died in 1932 and at his at his funeral his coffin was carried by eight Australian VCs. On his grave these words were cut:

'Captain Albert Jacka VC MC and Bar, 14th Battalion, AIF. The first VC in the Great War 1914-1918. A gallant soldier. An honoured citizen.'For years his old comrades of the 14th Battalion held a memorial service by his grave. After they passed on, that annual act of remembrance was continued by St Kilda Council, Melbourne. But perhaps the greatest tribute that was paid to Jacka was by another battalion historian, E J Rule, who called his book Jacka’s Mob, a title he explained in these words:

Not we only, but … the whole AIF came to look upon him as a rock of strength that never failed. We of the 14th Battalion never ceased to be thrilled when we heard ourselves referred to in the estaminet [French public house] or by passing units on the march as ‘some of Jack’s mob’.

[Rule, quoted in Stephen Snelling, VCs of the First World War: Gallipoli, 1995, p.119]

********************************************************************************

More than 8,000 Australians lost their lives in the ill-fated attempt

to force passage through the Dardanelles strait and capture the Turkish

capital, Constantinople.

The legends of Anzac heroism, mateship and ingenuity have gone down in folklore along with names like Simpson and Jacka VC.

Another part of that legend is the bungled landing in the wrong spot, the superior fighting skills of the bronzed diggers, and a defeat brought about as much because of dithering English commanders as the Turkish guns.

***********************************************************************************

According to military historians including Professor Peter Stanley of the University of NSW, one of the most persistent myths about the Anzac landing at Gallipoli is that the troops came ashore at the wrong spot.

Professor Stanley says the journalist and historian Charles Bean helped generate this myth by quoting a naval officer, Commander Dix, as saying, "the damn fools have landed us in the wrong place!"

Professor Stanley says this is "not correct". "For decades people have tried to explain the failure at Gallipoli by blaming it on the Royal Navy, but the Royal Navy did land the troops in approximately the right spot. It was what happened after the landing where things went wrong," he says.

The head of military history at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Ashley Ekins, agrees. "It's a common misconception," he says. "In fact, the Anzacs landed pretty well right in the centre of the originally selected landing zone."

Professor Stanley says there wasn't ever a precise landing spot, just a range of about a kilometre or two, and as it happened, putting the troops ashore around Anzac Cove was probably beneficial, because it was not heavily defended.

Mr Ekins, who is the author of the book Gallipoli; A Ridge Too Far, says there were incorrect claims at the time that currents drew the landing boats away from their intended target. "There are no currents in that area," he says.

Perhaps that theory is not held very credible for most people, nor written war diaries. The major problem would seem to be the sheer cliff faces that they had to climb over. Most plans showing the expected landing and the actual landing indicate huge margins of error, and the reasons why so many soldiers lost contact with their own battalions.

Another myth is that British generals were to blame for the failure of the Gallipoli campaign.

Wrong again, says Professor Stanley. "The first landing was opposed by only about 80 Turks, and the defenders were soon massively out-numbered, but the invaders failed to advance inland as they had been ordered," he says.

He says the Australians' orders were to push on and capture a hill called Maltepe, seven kilometres inland. But the Australian brigadiers got nervous and told their men to dig in on the second ridge, and that's where they stayed for the rest of the eight-month campaign.

Professor Stanley says Australians wanted to blame somebody else for a failure that was basically a failure of Australian command.

Mr Ekins says the then Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes, was among the first to point the finger at the British. In fact, Mr Ekins says, there are multiple reasons for why the campaign failed. "The objectives in the first place, the conception of the whole campaign, was flawed," he says.

Wartime inquiries found the entire campaign had been misconceived from the start and was poorly carried out, resulting in the useless deaths of tens of thousands of allied soldiers.

A 1917 British parliamentary report concluded: "The failure at Anzac was due mainly to the difficulties of the country and the strength of the enemy."

However it also noted that had the British been successful at nearby Suvla, they may have lessened Turkish resistance at Anzac Cove.

The Turks were expecting them to land in a different spot, and while they only had a limited number above Anzac Cove, it didn't take them long to reposition their soldiers. The first landing was in the dark, but landings continued for hours into the daylight.

Historian Joan Beaumont from the Australian National University says the reality was that the Anzacs were "not really a race of athletes as they were sometimes called".

Professor Beaumont says that although official war correspondent Charles Bean described them as being considerably fitter and taller than the men from the British working classes, in fact some of the physical standards weren't high by modern standards.

The minimum height for Australian soldiers from the start of the war was five feet six inches (167cms), and went down to a diminutive five feet (152cms) by the end of the war.

But while the Anzacs may not have been very tall, Mr Ekins says they were certainly fit. "They were undoubtedly a fine contingent of men," he says. "And they did stand out alongside the British troops... People noticed the difference in their bearing, their size and so on."

However Mr Ekins says they were not good soldiers, at least not at first. "At the outset when they landed they were actually very inexperienced amateurs. They had to learn in a very hard school and there was much about war that they had to learn."

Professor Beaumont, author of books including Broken Nation, says that it was Bean who helped create a misconception that the Anzacs were all bushmen, natural solders, fine horsemen and crack shots. "That's one of the key elements of the Anzac legend, but even at the time that Bean was writing the majority of Australians lived in the major towns," she says.

Professor Stanley also says while the Anzacs were the best physical specimens that could be found, they were mostly from the capital cities.

One theory that seems to be correct, in fact of all the war records sourced, the height of the men seemed to be rather less than today's heights. Most were around 5ft 6-7 inches.

A huge number came from the land, and their ability at horsemanship shone.

***********************************************************************************

Simpson and his Donkey

One of the heroes of the Gallipoli campaign is stretcher bearer John Simpson Kirkpatrick who famously used a donkey to carry wounded men back from the front line. Simpson landed at Anzac Cove on April 25, 1915, and was shot and killed by a sniper less than four weeks later.

Professor Stanley, author of the book Simpson's Donkey, says the Simpson story is a very confused one. For one thing, he says, it's probable there was more than one donkey.

"He'd joined up basically... to go back home to London to see his mother and sister, to whom he'd been writing for several years while working around the outback of Australia and in various places," Mr Ekins says.

"He joined up, became a soldier, a stretcher-bearer in the field ambulance and found himself on Gallipoli, to his surprise I guess, when he was intending to go back home to England."

He says contrary to the popular belief, Simpson may not have saved any lives.

"He did very brave work, he went into the gullies, he rescued men who were wounded, but mostly men with leg wounds," Mr Ekins says. "He may not have actually saved a single soldier who was going to die.

********************************************************************************

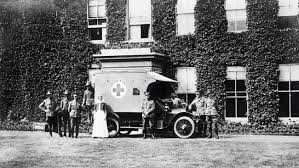

A man who certainly demonstrated the ANZAC spirit was a wealthy

Australian named Charles Billyard-Leake who, in 1914, was living at

Harefield Park: a large manor house in Middlesex, England.

A man who certainly demonstrated the ANZAC spirit was a wealthy

Australian named Charles Billyard-Leake who, in 1914, was living at

Harefield Park: a large manor house in Middlesex, England.

Charles was too old to join the army in 1914 (when World War I began), but he still wanted to support the war effort of his birth country.

He did this by allowing his house and its large, sprawling grounds to be used as a hospital for ANZAC soldiers. Throughout the war, and for six months after it finished, 50,000 ANZACs stayed at Harefield Hospital. The King and Queen of England also paid a visit in 1915.

Today the students from a local primary school, Harefield Junior School, are keeping this time in history alive by studying the stories of Australian soldiers who stayed at Harefield Hospital. The local village holds an ANZAC Day celebration every year, where children parade through the town before laying wreaths or flowers on some of the 111 graves of Australian soldiers and one nurse.

A flag from Harefield School was used to cover the coffins of the soldiers who died at Harefield Hospital. This flag now hangs in Adelaide High School in South Australia, as a sign of their shared history. During World War I, the Adelaide High School community sent parcels of food and money donations to every student and teacher at Harefield School. The two communities still keep in contact today.

He and his

medical

team set sail from Australia on the Runic, scheduled to arrive in mid

April 1915. Their first duty on arrival was to purchase the

necessary equipment for the Hospital, and to furnish and equip the

house ready for use by Australian troops by June 1915.

He and his

medical

team set sail from Australia on the Runic, scheduled to arrive in mid

April 1915. Their first duty on arrival was to purchase the

necessary equipment for the Hospital, and to furnish and equip the

house ready for use by Australian troops by June 1915.

The legends of Anzac heroism, mateship and ingenuity have gone down in folklore along with names like Simpson and Jacka VC.

Another part of that legend is the bungled landing in the wrong spot, the superior fighting skills of the bronzed diggers, and a defeat brought about as much because of dithering English commanders as the Turkish guns.

***********************************************************************************

Myths - There has to be someone who spoils the legendary!

According to military historians including Professor Peter Stanley of the University of NSW, one of the most persistent myths about the Anzac landing at Gallipoli is that the troops came ashore at the wrong spot.

Professor Stanley says the journalist and historian Charles Bean helped generate this myth by quoting a naval officer, Commander Dix, as saying, "the damn fools have landed us in the wrong place!"

Professor Stanley says this is "not correct". "For decades people have tried to explain the failure at Gallipoli by blaming it on the Royal Navy, but the Royal Navy did land the troops in approximately the right spot. It was what happened after the landing where things went wrong," he says.

The head of military history at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Ashley Ekins, agrees. "It's a common misconception," he says. "In fact, the Anzacs landed pretty well right in the centre of the originally selected landing zone."

Professor Stanley says there wasn't ever a precise landing spot, just a range of about a kilometre or two, and as it happened, putting the troops ashore around Anzac Cove was probably beneficial, because it was not heavily defended.

Mr Ekins, who is the author of the book Gallipoli; A Ridge Too Far, says there were incorrect claims at the time that currents drew the landing boats away from their intended target. "There are no currents in that area," he says.

Perhaps that theory is not held very credible for most people, nor written war diaries. The major problem would seem to be the sheer cliff faces that they had to climb over. Most plans showing the expected landing and the actual landing indicate huge margins of error, and the reasons why so many soldiers lost contact with their own battalions.

Another myth is that British generals were to blame for the failure of the Gallipoli campaign.

Wrong again, says Professor Stanley. "The first landing was opposed by only about 80 Turks, and the defenders were soon massively out-numbered, but the invaders failed to advance inland as they had been ordered," he says.

He says the Australians' orders were to push on and capture a hill called Maltepe, seven kilometres inland. But the Australian brigadiers got nervous and told their men to dig in on the second ridge, and that's where they stayed for the rest of the eight-month campaign.

Professor Stanley says Australians wanted to blame somebody else for a failure that was basically a failure of Australian command.

Mr Ekins says the then Australian prime minister, Billy Hughes, was among the first to point the finger at the British. In fact, Mr Ekins says, there are multiple reasons for why the campaign failed. "The objectives in the first place, the conception of the whole campaign, was flawed," he says.

Wartime inquiries found the entire campaign had been misconceived from the start and was poorly carried out, resulting in the useless deaths of tens of thousands of allied soldiers.

A 1917 British parliamentary report concluded: "The failure at Anzac was due mainly to the difficulties of the country and the strength of the enemy."

However it also noted that had the British been successful at nearby Suvla, they may have lessened Turkish resistance at Anzac Cove.

The Turks were expecting them to land in a different spot, and while they only had a limited number above Anzac Cove, it didn't take them long to reposition their soldiers. The first landing was in the dark, but landings continued for hours into the daylight.

Historian Joan Beaumont from the Australian National University says the reality was that the Anzacs were "not really a race of athletes as they were sometimes called".

Professor Beaumont says that although official war correspondent Charles Bean described them as being considerably fitter and taller than the men from the British working classes, in fact some of the physical standards weren't high by modern standards.

The minimum height for Australian soldiers from the start of the war was five feet six inches (167cms), and went down to a diminutive five feet (152cms) by the end of the war.

But while the Anzacs may not have been very tall, Mr Ekins says they were certainly fit. "They were undoubtedly a fine contingent of men," he says. "And they did stand out alongside the British troops... People noticed the difference in their bearing, their size and so on."

However Mr Ekins says they were not good soldiers, at least not at first. "At the outset when they landed they were actually very inexperienced amateurs. They had to learn in a very hard school and there was much about war that they had to learn."

Professor Beaumont, author of books including Broken Nation, says that it was Bean who helped create a misconception that the Anzacs were all bushmen, natural solders, fine horsemen and crack shots. "That's one of the key elements of the Anzac legend, but even at the time that Bean was writing the majority of Australians lived in the major towns," she says.

Professor Stanley also says while the Anzacs were the best physical specimens that could be found, they were mostly from the capital cities.

One theory that seems to be correct, in fact of all the war records sourced, the height of the men seemed to be rather less than today's heights. Most were around 5ft 6-7 inches.

A huge number came from the land, and their ability at horsemanship shone.

***********************************************************************************

Simpson and his Donkey

One of the heroes of the Gallipoli campaign is stretcher bearer John Simpson Kirkpatrick who famously used a donkey to carry wounded men back from the front line. Simpson landed at Anzac Cove on April 25, 1915, and was shot and killed by a sniper less than four weeks later.

Professor Stanley, author of the book Simpson's Donkey, says the Simpson story is a very confused one. For one thing, he says, it's probable there was more than one donkey.

"He'd joined up basically... to go back home to London to see his mother and sister, to whom he'd been writing for several years while working around the outback of Australia and in various places," Mr Ekins says.

"He joined up, became a soldier, a stretcher-bearer in the field ambulance and found himself on Gallipoli, to his surprise I guess, when he was intending to go back home to England."

He says contrary to the popular belief, Simpson may not have saved any lives.

"He did very brave work, he went into the gullies, he rescued men who were wounded, but mostly men with leg wounds," Mr Ekins says. "He may not have actually saved a single soldier who was going to die.

Simpson and his donkey

One man who exemplified the ANZAC spirit was Private John Simpson Kirkpatrick. Simpson, as he was known, was a stretcher-bearer in the Australian Army Medical Corps. Night or day, he rescued injured men from the battle line at Monash Valley and transported them to safety at ANZAC Cove on the back of his donkey. The donkey had originally been brought to Gallipoli for carrying water but, with Simpson, it found a much greater cause. In only 24 days at Gallipoli, Simpson and his donkey rescued around 300 wounded soldiers.********************************************************************************

Harefield Park – England

A man who certainly demonstrated the ANZAC spirit was a wealthy

Australian named Charles Billyard-Leake who, in 1914, was living at

Harefield Park: a large manor house in Middlesex, England.

A man who certainly demonstrated the ANZAC spirit was a wealthy

Australian named Charles Billyard-Leake who, in 1914, was living at

Harefield Park: a large manor house in Middlesex, England.Charles was too old to join the army in 1914 (when World War I began), but he still wanted to support the war effort of his birth country.

He did this by allowing his house and its large, sprawling grounds to be used as a hospital for ANZAC soldiers. Throughout the war, and for six months after it finished, 50,000 ANZACs stayed at Harefield Hospital. The King and Queen of England also paid a visit in 1915.

Today the students from a local primary school, Harefield Junior School, are keeping this time in history alive by studying the stories of Australian soldiers who stayed at Harefield Hospital. The local village holds an ANZAC Day celebration every year, where children parade through the town before laying wreaths or flowers on some of the 111 graves of Australian soldiers and one nurse.

A flag from Harefield School was used to cover the coffins of the soldiers who died at Harefield Hospital. This flag now hangs in Adelaide High School in South Australia, as a sign of their shared history. During World War I, the Adelaide High School community sent parcels of food and money donations to every student and teacher at Harefield School. The two communities still keep in contact today.

In November 1914 Mr and Mrs

Charles

Billyard-Leake, Australians resident in the UK, offered their home,

Harefield Park House and its grounds, to the Minister of Defence in

Melbourne for use as a convalescent home for wounded soldiers of the

Australian Imperial Forces (AIF). The offer was accepted by

the Commonwealth Defence

Department and the property became the No. 1 Australian Auxiliary

Hospital in December 1914. It was the only purely Australian hospital in England.

The Hospital consisted of

Harefield Park

House, a 3-storey plain brick building, some out-buildings and grounds

of some 250 acres. It was proposed that the Hospital would

accommodate 60 patients in the winter and 150 in the summer.

It

would be a rest home for officers and other ranks, and also a depot for

collecting invalided soldiers to be sent back to Australia.

The medical and nursing staff

comprised one

Captain from the Australian Army Medical Corps, one Sergeant, one

Corporal, four Privates (as wardsmen and orderlies), one Matron and

five Nursing Sisters. The Medical Superintendent was to be

under

the supervision of the High Commissioner.

The appointed Matron, Miss

Ethel Gray, and five nurses departed Australia on the RMS Osterley,

arriving in England at the end of March 1915. The first

Medical

Superintendent was Captain M.V. Southey, AAMC.

He and his

medical

team set sail from Australia on the Runic, scheduled to arrive in mid

April 1915. Their first duty on arrival was to purchase the

necessary equipment for the Hospital, and to furnish and equip the

house ready for use by Australian troops by June 1915.

He and his

medical

team set sail from Australia on the Runic, scheduled to arrive in mid

April 1915. Their first duty on arrival was to purchase the

necessary equipment for the Hospital, and to furnish and equip the

house ready for use by Australian troops by June 1915.

As Harefield Park House could

only

accommodate a quarter of the number expected, hutted wards were built

on the front lawn, and a mess hall for 120 patients in the courtyard.

By May 80 beds were ready.

The first 8 patients arrived on

2nd June

1915. By 22nd June the Hospital had 170 patients and extra

huts

were built. The first operation was performed in

July. In

August, when the Hospital had 362 patients, King George V and Queen

Mary visited for two hours, speaking to every patient confined to bed.

In September extra beds had to be found urgently for another

49

patients. An Artificial Limb workshop opened at Christmas.

In January 1916 an eye ward

opened. An

Orderlies Canteen opened for all ranks below Sergeant. A

Patients' Canteen had already been established and was run by a

Committee, including Mrs Letitia Sara Billyard-Leake and her daughter

Letitia, and ladies of the surrounding district.

By the end of March 1916 the

Hospital had

equipped 803 beds. In May Mr Billyard-Leake offered to rent

his

property The Red House in Park Lane, opposite the Officers' Mess, for

use as staff accommodation.

In October 1916 the Hospital

had 960

patients. In November it was recommended that,

rather than

remain a convalescent home, the

Hospital should become a general hospital complete with operating

theatres and an X-ray department. The staff now comprised one

Lieutenant-Colonel, five Majors, 12 Captains, one Quartermaster (an

Honorary Lieutenant), one Matron, two Head Sisters, 36 Staff Nurses,

one Warrant Officer, 15 Staff Sergeants and Sergeants, 10 Corporals and

94 Privates. Two dental units and six masseurs were attached

to

the Hospital. An X-ray attendant and a laboratory attendant

(both

Sergeants) were added later.

An Australian Red

Cross store

opened in December. A small magazine was produced by the

patients

which, in December 1916, became an official magazine - the Harefield Park Boomerang.

Initially published irregularly, it was finally established

as a monthly magazine. (The final issue, entitled The Victory Number,

was published in December 1918).

As the war progressed the

Hospital became a

general hospital. At the height of its use it accommodated

over

1000 patients and the nursing staff had expanded to 74 members.

By December 1917 the Hospital had three Lieutenant-Colonels,

namely the Commanding Officer, a surgeon-specialist and a radiologist

to the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF). It also had a large

number of voluntary workers.

By August 1918 the Hospital had

become a

centre for ear, nose and throat (ENT) and eye disorders. It

had

Massage and Dental Departments and an Electrical Department where

skiagrams (X-rays) could be obtained. The patients were

housed in

36 large huts dispersed throughout Harefield Park. Nearly 50

buildings were in use, including workshops, garages, stores, messes,

canteens, a recreation hall (where concerts and film shows were held),

a billiards rooms, writing rooms, a library, a cookhouse, a detention

room and a mortuary.

For entertainment, tours to London were

arranged and paid for out of canteen funds, and the ladies of the

district made their cars available for country trips, picnics and

journeys to and from the railway station, both for patients and

visitors.

The Hospital gradually closed

down during

January 1919. The Hospital records were returned to Australia

after the war and are now lodged in the Australian War

Memorial Library.

No comments:

Post a Comment