The Background to the Zulu Wars from wikipedia is included for the benefit of following Anthony Durnfords timelines, and for those who might be unaware of the "behind the scenes" activities.

The Background to the Zulu Wars from wikipedia is included for the benefit of following Anthony Durnfords timelines, and for those who might be unaware of the "behind the scenes" activities.

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British and the Zulus. Following Lord Carnarvon's successful introduction of federation in Canada, it was thought that similar political effort, coupled with military campaigns, might succeed with the African kingdoms, tribal areas and Boer republics in South Africa.

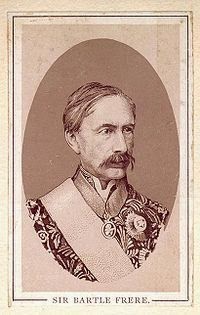

In 1874, Sir Henry Bartle Frere was sent to South Africa as High Commissioner for the British Empire to bring such plans into being. Among the obstacles were the presence of the independent states of the South African Republic and the Kingdom of Zululand and its army.

Frere, on his own initiative, without the approval of the British government and with the intent of instigating a war with the Zulu, had presented an ultimatum on 11 December 1878, to the Zulu king Cetshwayo

with which the Zulu king could not comply. Bartle Frere then sent Lord Chelmsford to

invade Zululand.

Frere, on his own initiative, without the approval of the British government and with the intent of instigating a war with the Zulu, had presented an ultimatum on 11 December 1878, to the Zulu king Cetshwayo

with which the Zulu king could not comply. Bartle Frere then sent Lord Chelmsford to

invade Zululand. The war is notable for several particularly bloody battles, including a stunning opening victory by the Zulu at the Battle of Isandlwana, as well as for being a landmark in the timeline of imperialism in the region. The war eventually resulted in a British victory and the end of the Zulu nation's independence.

Frere was sent to South Africa as High Commissioner to bring it about. One of the obstacles to such a scheme was the presence of the independent states of the South African Republic, informally known as the Transvaal Republic, and the Kingdom of Zululand. Bartle Frere wasted no time in putting the scheme forward and manufacturing a casus belli against the Zulu by exaggerating the significance of a number of recent incidents.

|

| Shepstone |

Shepstone, in his capacity as British governor of Natal, had expressed concerns about the Zulu army under King Cetshwayo and the potential threat to Natal — especially given the adoption by some of the Zulus of old muskets and other out of date firearms. In his new role of Administrator of the Transvaal, he was now responsible for protecting the Transvaal and had direct involvement in the Zulu border dispute from the side of the Transvaal. Persistent Boer representations and Paul Kruger's diplomatic manoeuvrings added to the pressure.

There were incidents involving Zulu paramilitary actions on either

side of the Transvaal/Natal border, and Shepstone increasingly began to regard

King Cetshwayo, as having permitted such "outrages," and to be in a

"defiant mood." King Cetshwayo now found no defender in Natal save

Bishop John William Colenso.

There were incidents involving Zulu paramilitary actions on either

side of the Transvaal/Natal border, and Shepstone increasingly began to regard

King Cetshwayo, as having permitted such "outrages," and to be in a

"defiant mood." King Cetshwayo now found no defender in Natal save

Bishop John William Colenso.Colenso advocated for native Africans in Natal and Zululand who had been unjustly treated by the colonial regime in Natal. In 1874 he took up the cause of Langalibalele and the Hlubi and Ngwe tribes in representations to the Colonial Secretary, Lord Carnarvon.

|

| Robben Island |

Langalibalele had been falsely accused of rebellion in 1873

and, following a charade of a trial, was found guilty and imprisoned on Robben

Island.

Langalibalele had been falsely accused of rebellion in 1873

and, following a charade of a trial, was found guilty and imprisoned on Robben

Island.  |

| Another prisoner another time |

In taking the side of Langalibalele against the Colonial regime in Natal and Theophilus Shepstone, the Secretary for Native Affairs, Colenso found himself even further estranged from colonial society in Natal.

Bishop Colenso's concern about the misleading information that was being provided to the Colonial Secretary in London by Shepstone and the Governor of Natal prompted him to champion the cause of the Zulus against Boer oppression and official encroachments. He was a prominent critic of Sir Bartle Frere's efforts to depict the Zulu kingdom as a threat to Natal. Colenso's campaigns revealed the dark, racist foundation underpinning the colonial regime in Natal and made him enemies among the colonists.

British Prime Minister Disraeli's Tory administration in London did not want a war with the Zulus.

"The fact is," wrote Sir Michael Hicks Beach, who would replace Carnarvon as Secretary of State for the Colonies, in November 1878, "that matters in Eastern Europe and India ... wore so serious an aspect that we cannot have a Zulu war in addition to other greater and too possible troubles."

However Sir Bartle Frere had already been into the Cape Colony as governor and high commissioner since 1877 with the brief of creating a Confederation of South Africa from the various British colonies, Boer Republics and native states and his plans were well advanced. He had concluded that the powerful Zulu kingdom stood in the way of this, and so was receptive to Shepstone's arguments that King Cetshwayo and his Zulu army posed a threat to the peace of the region. Preparations for a British invasion of the Zulu kingdom had been underway for months.

In December 1878, notwithstanding the reluctance of the British government to start yet another colonial war, Frere presented Cetshwayo with an ultimatum that the Zulu army be disbanded and the Zulus accept a British resident. This was unacceptable to the Zulus as it effectively meant that Cetshwayo, had he agreed, would have lost his throne.

Shepstone claimed to have evidence supporting the Boer position but, ultimately, he failed to provide any. In a meeting with Zulu notables at Blood River in October 1877, Shepstone attempted to placate the Zulu with paternal speeches, however they were unconvinced and accused Shepstone of betraying them. Shepstone's subsequent reports to Carnarvon then began to paint the Zulu as an aggressive threat where he had previously presented Cetshwayo in a most favourable light.

In February 1878 a commission was appointed by Henry Bulwer, the lieutenant-governor of Natal since 1875, to report on the boundary question. The commission reported in July and found almost entirely in favour of the contention of the Zulu.

However, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, then high commissioner and still pressing forward with Carnarvon's federation plan, characterized the award as "one-sided and unfair to the Boers,"stipulated that on the land being given to the Zulu, the Boers living on it should be compensated if they left or protected if they remained.

In addition, Frere planned to use the meeting on the boundary commission report with the Zulu representatives to also present a surprise ultimatum he had devised that would allow British forces under Lord Chelmsford, which he had previously been instructed to use only in defense against a Zulu invasion of Natal, to instead invade Zululand. Three incidents occurred in late July, August and September which Frere seized upon as his casus belli and were the basis for the ultimatum to which Frere knew Cetshwayo could not comply, giving Frere a pretext to attack the Zulu kingdom.

The first two incidents related to the flight into Natal of two wives of Sihayo kaXonga and their subsequent seizure and execution by his brother and sons and were described thus:

"A wife of the chief Sihayo

had left him and escaped into Natal. She was followed [on 28 July 1878] by a

party of Zulus, under Mehlokazulu, the chief son of Sihayo, and his brother,

seized at the kraal where she had taken refuge, and carried back to Zululand,

where she was put to death, in accordance with Zulu law...

"A week later the same young

men, with two other brothers and an uncle, captured in like manner another

refugee wife of Sihayo, in the company of the young man with whom she had fled.

This woman was also carried back, and is supposed to have been put to death

likewise; the young man with her although guilty in Zulu eyes of a most heinous

crime, punishable with death, was safe from them on English soil; they did not

touch him."

The third incident occurred in September, when two men were detained while

on a sand bank of the Thukela River near the Middle Drift. Sir Bartle Frere

described this matter in a despatch to Sir Michael Hicks Beach, who

had replaced Carnarvon as Secretary of State for the Colonies:

"Mr. Smith, a surveyor in

the Colonial Engineer Department, was on duty inspecting the road down to the

Tugela, near Fort Buckingham, which had been made a few years ago by order of

Sir Garnet Wolseley, and accompanied by Mr. Deighton, a trader, resident at

Fort Buckingham, went down to the ford across the Tugela. The stream was very

low, and ran under the Zulu bank, but they were on this side of it, and had not

crossed when they were surrounded by a body of 15 or 20 armed Zulus, made

prisoners, and taken off with their horses, which were on the Natal side of the

river, and roughly treated and threatened for some time; though, ultimately, at

the instance of a headman who came up, they were released and allowed to

depart."

By themselves, these incidents were flimsy grounds upon which to found an

invasion of Zululand. Bulwer did not initially hold Cetshwayo responsible for

what was clearly not a political act in the seizure and murder of the two

women.

"I have sent a message to

the Zulu King to inform him of this act of violence and outrage by his subjects

in Natal territory, and to request him to deliver Up to this Government to be

tried for their offence, under the laws of the Colony, the persons of

Mehlokazulu and Bekuzulu the two sons of Sirayo who were the leaders of the

party."

Cetshwayo also treated the complaint rather lightly, responding

"Cetywayo is sorry to have

to acknowledge that the message brought by Umlungi is true, but he begs his

Excellency will not take it in the light he sees the Natal Government seem to

do, as what Sirayo’s sons did he can only attribute to a rash act of boys who

in the zeal for their father’s house did not think of what they were doing.

Cetywayo acknowledges that they deserve punishing, and he sends some of his izinduna, who

will follow Umlungi with his words. Cetywayo states that no acts of his

subjects will make him quarrel with his fathers of the house of Shaka."

The original complaint carried to Cetshwayo from the lieutenant-governor was

in the form of a request for the surrender of the culprits. The request was

subsequently transformed by Sir Bartle Frere into a 'demand'. Frere wrote to

Hicks Beach, 30 September 1878:

"Apart from whatever may be

the general wish of the Zulu nation, it seems to me that the seizure of the two

refugee women in British territory by an armed force crossing an unmistakable

and well known boundary line, and carrying them off and murdering them with

contemptuous disregard for the remonstrances of the Natal policemen, is itself

an insult and a violation of British territory which cannot be passed over, and

unless apologised and atoned for by compliance with the Lieutenant Governor’s

demands, that the leaders of the murderous gangs shall be given up to justice,

it will be necessary to send to the Zulu King an ultimatum which must put an

end to pacific relations with our neighbours."

In reply, in at least three dispatches, 17 October, 21 November and 18

December, Hicks Beach emphatically states that war is to be avoided and a

British invasion of Zululand prohibited. From 21 November dispatch:

"... Her Majesty's

Government have arrived, it is my duty to impress upon you that in supplying

these reinforcements it is the desire of Her Majesty's Government not to

furnish means for a campaign of invasion and conquest, but to afford such

protection as may be necessary at this juncture to the lives and property of

the colonists. Though the present aspect of affairs is menacing in a high

degree, I can by no means arrive at the conclusion that war with the Zulus

should be unavoidable, and I am confident that you, in concert with Sir H.

Bulwer, will use every effort to overcome the existing difficulties by judgment

and forbearance, and to avoid an evil so much to be deprecated as a Zulu war.".

Frere has been accused of chicanery by taking deliberate advantage of the

length of time it took for correspondence to pass between South Africa and

London to conceal his intentions from his political masters or at least defer

giving them the necessary information until it was too late for them to act.The first intimation to the British government of his intention to make 'demands' on the Zulu was in a private letter to Hicks Beach written on 14 October 1878. The letter only arrived in London on 16 November and by then messengers had already been despatched from Natal to the Zulu king to request the presence of a delegation at the Lower Tugela on 11 December for the purpose of receiving the Boundary Commission’s findings.

Had Hicks Beach then sent off a telegraph forbidding any action other than the announcement of the boundary award, it might have arrived in South Africa just in time to prevent the ultimatum being presented. No prohibition was sent and could hardly be expected to have been, for Hicks Beach had no means of knowing the urgency of the events that were in train.

Nowhere in Frere’s letter was there anything to indicate how soon he intended to act, nor was there anything to suggest how stringent his demands would be.

In January 1879 Hicks Beach wrote to Bartle Frere:

"I may observe that the

communications which had previously been received from you had not entirely

prepared them" (Her Majesty's Government) "for the course which you

have deemed it necessary to take. The representations made by Lord Chelmsford

and yourself last autumn as to the urgent need of strengthening Her Majesty's

forces in South Africa were based upon the imminent danger of an invasion of

Natal by the Zulus, and the inadequate means at that time at your disposal for

meeting it.

In order to afford protection to the lives and property of the colonists, the reinforcements asked for were supplied, and, in informing you of the decision of Her Majesty's Government, I took the opportunity of impressing upon you the importance of using every effort to avoid war. But the terms which you have dictated to the Zulu king, however necessary to relieve the colony in future from an impending and increasing danger, are evidently such as he may not improbably refuse, even at the risk of war; and I regret that the necessity for immediate action should have appeared to you so imperative as to preclude you from incurring the delay which would have been involved in consulting Her Majesty's Government upon a subject of so much importance as the terms which Cetywayo should be required to accept before those terms were actually presented to the Zulu king."

Hicks Beach had earlier admitted his helplessness with regard to the Frere's

actions in a telling note to his Prime Minister:In order to afford protection to the lives and property of the colonists, the reinforcements asked for were supplied, and, in informing you of the decision of Her Majesty's Government, I took the opportunity of impressing upon you the importance of using every effort to avoid war. But the terms which you have dictated to the Zulu king, however necessary to relieve the colony in future from an impending and increasing danger, are evidently such as he may not improbably refuse, even at the risk of war; and I regret that the necessity for immediate action should have appeared to you so imperative as to preclude you from incurring the delay which would have been involved in consulting Her Majesty's Government upon a subject of so much importance as the terms which Cetywayo should be required to accept before those terms were actually presented to the Zulu king."

"I have impressed this

[non-aggressive] view upon Sir B. Frere, both officially and privately, to the

best of my power. But I cannot really control him without a telegraph (I don’t

know that I could with one) I feel it is as likely as not that he is at war

with the Zulus at the present moment."

Frere wanted to provoke a conflict with the Zulus and in that goal he

succeeded. Cetshwayo rejected the demands of 11 December, by not responding by

the end of the year. A concession was granted by Bartle Frere until 11 January

1879, after which Bartle Frere deemed a state of war to exist.The British forces intended for the defense of Natal had already been on the march with the intention to attack the Zulu kingdom. On 10 January they were poised on the border. On 11 January, they crossed the border and invaded Zululand.

The terms of the ultimatum

The terms which were included in the ultimatum delivered to the representatives of King Cetshwayo on the banks of the Thukela river on 11 December 1878. No time was specified for compliance with item 4, twenty days were allowed for compliance with items 1–3, that is, until 31 December inclusive; ten days more were allowed for compliance with the remaining demands, items 4–13. The earlier time limits were subsequently altered so that all expired on 10 January 1879.- Surrender of Sihayo’s three sons and brother to be tried by the Natal courts.

- Payment of a fine of five hundred head of cattle for the outrages committed by the above and for Cetshwayo’s delay in complying with the request of the Natal Government for the surrender of the offenders.

- Payment of a hundred head of cattle for the offence committed against Messrs. Smith and Deighton.

- Surrender of the Swazi chief Umbilini and others to be named hereafter, to be tried by the Transvaal courts.

- Observance of the coronation promises.

- That the Zulu army be disbanded and the men allowed to go home.

- That the Zulu military system be discontinued and other military regulations adopted, to be decided upon after consultation with the Great Council and British Representatives.

- That every man, when he comes to man’s estate, shall be free to marry.

- All missionaries and their converts, who until 1877 lived in Zululand, shall be allowed to return and reoccupy their stations.

- All such missionaries shall be allowed to teach and any Zulu, if he chooses, shall be free to listen to their teaching.

- A British Agent shall be allowed to reside in Zululand, who will see that the above provisions are carried out.

- All disputes in which a missionary or European is concerned, shall be heard by the king in public and in presence of the Resident.

- No sentence of expulsion from Zululand shall be carried out until it has been approved by the Resident.

The pretext for the war had its origins in border disputes between the Zulu leader, Cetshwayo, and the Boers in the Transvaal region. Following a commission enquiry on the border dispute which reported in favour of the Zulu nation in July 1878, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, acting on his own, added an ultimatum to the commission meeting, much to the surprise of the Zulu representatives who then relayed it to Cetshwayo.

Cetshwayo had not responded by the end of the year, so an extension was granted by Bartle Frere until 11 January 1879. Cetshwayo returned no answer to the preposterous demands of Bartle Frere, and in January 1879 a British force under Lieutenant General Frederick Augustus Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford invaded Zululand, without authorisation by the British Government.

Lord Chelmsford, the Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the war, initially planned a five-pronged invasion of Zululand composed of over 15,000 troops in five columns and designed to encircle the Zulu army and force it to fight as he was concerned that the Zulus would avoid battle.

In the event, Chelmsford settled on three invading columns with the main center column, now consisting of some 7800 men comprising the previously called No. 3 Column and Durnford's No.2 Column, under his direct command.

He moved his troops from Pietermaritzburg to a forward camp at Helpmekaar, past Greytown. On 9 January 1879 they moved to Rorke's Drift, and early on 11 January commenced crossing the Buffalo River into Zululand.

Three columns were to invade Zululand, from the Lower Tugela, Rorke's Drift, and Utrecht respectively, their objective being Ulundi, the royal capital.

***********************************************************************************

The following information is from a colonist whose character

and experience render him an unexceptionable witness:

He says, "As a

resident of many years in Zululand, I have had some experience and means of

observation. The year before the Commission sat at Rorke's Drift, the chief

Usirayo built his head kraal at Usogexe, and a strong stone wall with loopholes

round it; and his people often told me that they hoped to use them against the

white men. They often talked about war; and I more than once remonstrated with

Usirayo and his people, telling them that they should take care not to bring

about a war with 'abelungu' (the white men), as it would be worse for

themselves, but in vain, as they felt confident in their guns and their

numbers.

Cetywayo once sent an ox-hide to Sir T. Shepstone, and said, if he

could count the hair on it, he would perhaps be able to form an idea of the

number of the Zulu warriors; but I do not think the hide reached its

destination. When the Commission was sitting at Rorke's Drift, Usirayo

threatened to destroy the men and tents, if they came across the Buffalo to

inspect the border line, near Usirayo's head kraal, where you still see the

stone heaps left since the beacons.

I warned the Commission through a

missionary, and the late Colonel Durnford noted it. The Zulus have bought their

thousands of guns, for the purpose of using them against the whites; have

bought most of their ammunition with the same intention; have engaged people

from Basutoland to teach them to make powder; and they have had a good deal of

training in shooting.

********************************************************************************

Bibliography

- Dutton, Roy (2010). Forgotten Heroes: Zulu & Basuto Wars including Complete Medal Roll. Infodial. ISBN 978-0-9556554-4-9.

- Barthorp, Michael (2002). The Zulu War: Isandhlwana to Ulundi. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36270-0.

- Brookes, Edgar H; Webb, Colin de B. (1965). A History of Natal. Brooklyn: University of Natal Press. ISBN 0-86980-579-7.

- Colenso, Frances E. (1880). History of the Zulu War and Its Origin. Assisted by Edward Durnford. London: Chapman & Hall.

- David, Saul (February 2009). "The Forgotten Battles of the Zulu War". BBC History Magazine 10 (2). pp. 26–33.

- Gump, James O. (1996). The Dust Rose Like Smoke: The Subjugation Of The Zulu And The Sioux. Bison Books. ISBN 0-8032-7059-3.

- Knight, Ian (2003). The Anglo-Zulu War. Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-612-7.

- Knight, Ian; Castle, Ian (2004). Zulu War. Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-858-8.

- Laband, John; Knight, Ian (1996). The Anglo-Zulu War. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-86985-829-7.

- Lock, Ron; Peter Quantrill (2002). Zulu Victory: The Epic of Isandlwana and the Cover-up. Johannesburg & Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers. ISBN 1-86842-214-3.

- Martineau, John (1895). The Life and Correspondence of the Sir Bartle Frere. John Murray.

- Morris, Donald R. (1998). The Washing of the Spears. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80866-8.

- Raugh, Harold E. Jr. (2011). Anglo-Zulu War 1879: A Selected Bibliography. Scarecrow PressPress. ISBN 0-8108-7227-7.

- Spiers, Edward M. (2006). The Scottish Soldier and Empire, 1854–1902. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2354-9.

- Thompson, Paul Singer (2006). Black Soldiers of the Queen: The Natal Native Contingent in the Anglo-Zulu War. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-5368-2

No comments:

Post a Comment