General Frederic Augustus Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford

Order of the Bath (GCB), Royal Victorian Order (GCVO), (31 May 1827 –

9 April 1905) was a British general, best known for his commanding role during

the Anglo-Zulu

war.

General Frederic Augustus Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford

Order of the Bath (GCB), Royal Victorian Order (GCVO), (31 May 1827 –

9 April 1905) was a British general, best known for his commanding role during

the Anglo-Zulu

war.

The centre column of his forces was defeated at the Battle of Isandlwana, an unanticipated victory

for the Zulu and the British army's worst ever defeat from a technologically

inferior indigenous force. He would avenge his defeat at the Battle

of Ulundi which ended the Zulu campaign. He was awarded the GCB in August

1879.

Career

He wished to pursue a military career, and after unsuccessfully trying to obtain a place in the Grenadier Guards, he purchased (1844) a commission in the Rifle Brigade. He served (1845) with the Rifles in Halifax, Nova Scotia before purchasing an exchange (November 1845) into the Grenadiers as Ensign and Lieutenant.He was promoted Lieutenant and Captain in 1850, and became aide-de-camp (1852) to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Eglinton, and then to the Commander-in-Chief in Ireland, Sir Edward Blakeney, from 1853 to 1854.

Crimean War

In May 1855, he left for the Crimean

War, in which he served firstly with his battalion, then as

aide-de-camp (from July 1855) to the commander of the 2nd Division, Lieutenant-General

Edwin

Markham, and finally as deputy assistant quartermaster general (from

November 1855) on the staff at Headquarters, being promoted brevet Major.

He was mentioned in despatches and received the fifth class of the Turkish Order of the Medjidie and the British, Turkish and Sardinian Crimean medals.

Indian Rebellion of 1857

In 1857, he was promoted Captain and Lieutenant-Colonel, and transferred

(1858), as a Lieutenant-Colonel, to the 95th (Derbyshire)

Regiment of Foot, serving with that regiment at the end of the Indian

Mutiny, for which he was again mentioned in dispatches. He served as

deputy adjutant general (from 1861 to 1862) to the forces in Bombay, and

was promoted brevet Colonel in 1863.

There, he befriended the then governor of Bombay, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, and this relationship would be important later when serving in South Africa. He served, again as deputy adjutant general, in the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia, for which he was awarded the Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) and made an aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria in 1868. He was adjutant general in the East Indies from 1869 to 1874.

He returned to England in 1874 as colonel on the staff, commanding the forces at Shorncliffe Army Camp, and was appointed to command a brigade at Aldershot, with the temporary rank of Brigadier-General, in 1877. He had however requested a posting overseas in order to benefit from the cheaper cost of living.

Anglo-Zulu Wars

He was promoted to Major-General (March 1877), appointed to command the

forces in South Africa with the local rank of Lieutenant-General (February

1878), and in October succeeded his father as 2nd Baron Chelmsford.

He brought the Ninth Cape Frontier War to its completion in July 1878, and was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) (November 1878). His experiences fighting against the Xhosa confirmed his low opinion of the fighting capabilities of black Africans, a mistake that would come back to haunt him.

His friend, Sir Bartle Frere, engineered a war (January 1879) against a previous British ally, King Cetshwayo. Chelmsford's forces approached the Zulu at Isandlwana in a three columns formation.

The Zulu overran the centre column, reduced the effectiveness of the British by this division which allowed the Zulu to concentrate their military action on the poorly defended army camp. The engagement was an unexpected victory for the Zulu; the worst defeat of the British army with a technologically inferior indigenous force and the first incursion into Zululand.

The defeat concerned the British that an incursion by the Natal could result, so, Chelmsford was relieved of his command and replaced by Sir Garnet Wolseley.

The order could not be implemented until the arrival of Wolseley. Chelmsford ignored the peace offers from Cetshwayo and wanted to strike the Zulu at Ulundi to regain his reputation and end the campaign before Wolseley could remove him from command of the army.

Chelmsford left for England in July 1879 and Wolseley disclosed in his despatches that Thesiger should receive all the credit for the Ulundi success; he was awarded the GCB in August.

Lord Chelmsford became Lieutenant-General in 1882, Lieutenant of the Tower of London (1884 until 1889), colonel of the 4th (West London) Rifle Volunteer Corps (1887), full General (1888), and colonel of the Derbyshire Regiment (1889).

He exchanged the colonelcy of the Derbyshires for that of the 2nd Life Guards (1900), and was made GCVO (1902). He was the inaugural Governor and Commandant of the Church Lads' Brigade, a post he held until his death.

Sir Garnet Wolseley He replaced Chelmsford in South Africa.

From "Sir Garnet Wolseley: Victorian Hero" by Halik Kochanski

"Wolseley and his staff reached Cape Town on 23rd June 1879. There he received two pieces of important information, the first was that the Zulus had killed Louis, The Prince Imperial and son of Napoleon III and that there was to be a court of enquiry into the incident; the second was that, after months of relative inactivity, the news that he was about to be superseded had spurred Chelmsford into action.

Chelmsford no planned to advance on King Cetshwayo's kraal at his capital Ulundi on 1st June with three times the number of men that had accompanied him on the first invasion into Zululand in January.

Wolsely was appalled by both pieces of news. He wrote to his wife expressing sympathy for Empress Eugenie, the mother of the Prince Imperial. He was also dismayed to find that although Chelmsford was now invading Zululand with only two columns, one under Chelmsford himself and one under Major General Henry Crealock instead of the four of the January invasion, the columns were again operating independently and with no means of communicating and supporting each other.

Disaster appeared imminent so Wolseley made all haste to Durban as quickly as possible to travel overland to the seat of the war.

He sent orders to Crealock and Chelmsford, ordering them to stop all operations and not to communicate directly with England or South Africa without his permission. Chelmsford received his telegram on 2nd July when he was only four miles from Ulundi.

Wolseley arrived at Durban on 28th June and immediately travelled to Pietermaritzburg where he was sworn in as a High Commissioner. Two days later he met seventy native chiefs from Natal to win their support for the transport of supplies.

At Pietermaritzburg he heard that Chelmsford was only seventeen miles from Ulundi and Crealock's column was much further away. Wolseley rushed back to Durban to board a ship that would take him to Port Durnford, on the Zululand coast. With rough weather he was not able to land, and he was forced to return to Durban and to travel overland to Port Durnford.

There he met John Dunn who had lived among the Zulus an whom he heard was a power in Zululand and intended using him as much as possible. While he was attempting to reach Zululand, Chelmsford, in complete disobedience to Wolseley's order, reached Ulundi with 4000 British soldiers and 1000 native allies.

On 4th July he attacked and defeated the Zulu army of an estimated number of 20,000.

Wolseley received the news and was delighted that the war was over. However, Chlmsford had made no attempt to hold Ulundi nor to capture Cetshwayo, who had escaped when it was clear the Zulus would be defeated.

Chelmsford was censured by Wolseley for these failures, although he argued that Wolseley had given him no orders on what to do after the battle had been won. That was true, because Chelmsford had been given orders not to fight the battle until Wolseley had arrived."

***********************************************************************************

Let's consider Chelmsford's relationship with Anthony Durnford.

"Rorke's Drift" Adrian Greaves

He writes:

"Chelmsford was critical of many of the officers and afficials and wished they would be more like his friends, Evelyn Wood and Buller. He was annoyed with Anthony's role on the Boundary Commission once it found in favour of the Zulus and he was to find further fault with Durnford's actions in the days leading up to the Invasion.

In one attack he threatened to remove Durnford from his command. He then had no difficulty on laying blame for his defeat on someone whom he desliked and who was now dead.

It would seem the Chelmsford had bouts of depression, perhaps being bipolar.

He considered the option of resigning and wrote to Duke of Cambridge and Colonel Frederick Stanley Secretary of Sate for War. He advised..."that an officer of the rank of Major General should be sent to South Africa without delay. Sir Garnet Wolseley was that replacement.

Meanwhile in Britain there were relentless personal attacks on him by the newspapers, which blamed for for the loss of the camp, despite the exoneration given by the Court of Enquiry, which he convened solely to report back to him.

He became hurt and shaken by the vitriolic attacks on his reputation, attacks which eroded his confidence. His friends advised him to retire on health grounds, but after his friend Wood's victory at Khambula, and the arrival of more troops, Chelmsford recovered his determination to defeat the Zulus.

He decided to lead a column to relieve Col Pearson's besieged force at Eshow. His men fought off a large Zulu force at Gingindlovu and inflicted many fatalities on the fleeing Zulus.

His next task was return to Isandlwana and face the unburied remains. With a large burial party they recovered the precious wagons which were needed for the re-invasion of Zululand. Chelmsford had a long running feud with the civilian authorities in Natal, and both he and the civilians sent dispatches to the British government, which revealed that there was a lack of leadership and determination to end the conflict"

*********************************************************************************

It doesn't take much to realise that Lord Chelmsford certainly has problems and it doesn't take much after reading the press reports of the times, to realise that something is not quite right and to pose some questions.

Whether he had depression, or had a particular personality style, or was bi-polar who knows, but what is very clear is:

1. He had a very strong dislike of Anthony Durnford. Why?

Was it is qualifications as a Royal Engineer?

As a Royal Engineer, it was one of Anthony's strengths, after all he had been responsible for the building and designing of roads in Ceylon in 1851. His father had been responsible for the survey of Ireland. His great uncle Elias Durnford laid out the town of Pensacola in the US, amongst others.

Elias's son Elias Walker Durnford was responsible for huge projects including the canals in Canada, and his great grandfather Andrew Durnford worked on Dunkirk, Portsmouth and West Indies.

Just perhaps he had the ability and qualifications for surveying! And he certainly wasn't happy with the Boundary Commissioners findings.

2. Was it because he had an affinity with the natives, and cared about his men and their safety?

Consider that Anthony built the fort at Port Durnford, road works and many other engineering projects.. He didn't do it on his own, and would have relied on local workers. A lot can be gained from such experiences, if one's mindset allows. Perhaps the members of the Natal preferred to work with Anthony, who had empathy with them, than with someone whose whole reason was to prove a point and win a war, never mind who gets hurt along the way.

3. He was upset at the vitriol which was being directed his way

Now that is certainly something that Anthony's family would have felt then, and now, about what accusations that Chelmsford made about him. It spurred them to begin to ask questions, and not to stop until the truth had been revealed.

4. Was he capable of following orders?

On several occasions he ignored orders.

5. Was he caring of his fellow officers?

He was at Isandhlwana the night after the battle. Not once did he make any attempt to bury his dead. In fact from some reports he showed a very nonchalant attitude, and eager to confer with others before making statements. He left Rorke's Drift camp on the 23rd, without appointing anyone in charge.

6. Was he responsible enough to carry out his role?

Before he finally left South Africa his friends told Wolseley that Chelmsford was not fit to be a corporal, so they obviously thought so.

If the loss of the Zulu War wasn't bad enough for Chelmsford, the worst was probably still to come.

*********************************************************************************

Briefly, Napoleon Bonaparte I became the first Emperor of the French and he was King of Italy. Italy had lost all its kingdoms to the Charlemagnes and Franks, our ancestors before William invaded England in 1066. Then the English ruled France and it seemed everyone was at war with every one else. Britain and France particularly so.

Napolean I became the ruler in 1799. In 1805 Britain defeated his Navy at the Battle of Trafalgur. and in 1815 Lord Nelson beat him in the Battle of Waterloo. Then of course there was the French Revolution, and more battles, the Crimean War until finally in 1848 his nephew Napoleon III became ruler of France.

Napolean I became the ruler in 1799. In 1805 Britain defeated his Navy at the Battle of Trafalgur. and in 1815 Lord Nelson beat him in the Battle of Waterloo. Then of course there was the French Revolution, and more battles, the Crimean War until finally in 1848 his nephew Napoleon III became ruler of France.This story is about his son

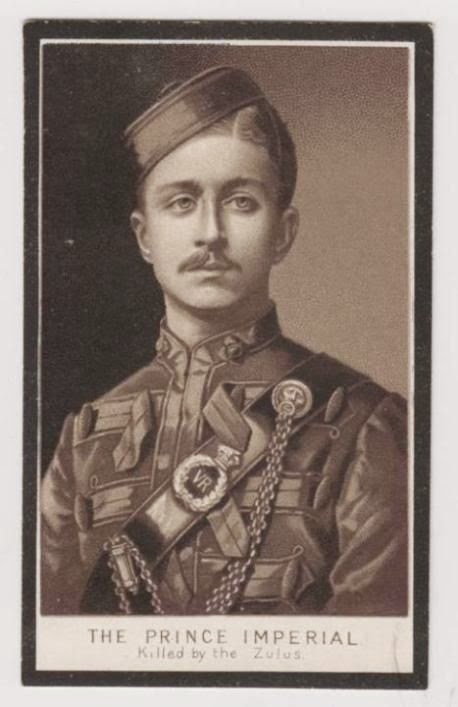

Napoléon, Prince Imperial (Full name: Napoléon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph Bonaparte, 16 March 1856 – 1 June 1879), prince impérial de France, was the only child of Emperor Napoleon III of France and his Empress consort Eugénie de Montijo.

Napoléon, Prince Imperial (Full name: Napoléon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph Bonaparte, 16 March 1856 – 1 June 1879), prince impérial de France, was the only child of Emperor Napoleon III of France and his Empress consort Eugénie de Montijo.At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871, he accompanied his father to the front and first came under fire at Saarbrücken. When the war began to go against the Imperial arms, however, his father sent him to the border with Belgium.

In September he sent him a message to cross over into Belgium. He travelled from there to England, arriving on 6 September, where he was joined by his parents. The Royal family settled in England at Camden Place in Chislehurst, Kent. On his father's death, Bonapartists proclaimed him Napoleon IV

On his 18th birthday, a large crowd gathered to cheer him at Camden Place.

The Prince Imperial attended elementary lectures in physics at King's College London. In 1872, he applied and was accepted to the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He finished seventh in his class of thirty four, and came top in riding and fencing. He was then commissioned into the Royal Artillery in order to follow in the footsteps of his famous great-uncle.

The Prince Imperial attended elementary lectures in physics at King's College London. In 1872, he applied and was accepted to the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. He finished seventh in his class of thirty four, and came top in riding and fencing. He was then commissioned into the Royal Artillery in order to follow in the footsteps of his famous great-uncle.On his father's death in January 1873, he was proclaimed Napoleon IV, Emperor of the French by the Bonapartist faction.

Keen to see action, he successfully put pressure on the British to allow him to participate in the Anglo-Zulu war. In 1879, serving with British forces, he was killed in a skirmish with a group of Zulus. His early death sent shockwaves throughout Europe, as he was the last serious dynastic hope for the restoration of the Bonapartes to the throne of France.

During the 1870s, there was some talk of a marriage between him and Queen Victoria's youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice. Victoria also reportedly believed that it would be best for "the peace of Europe" if the prince became king of France.

During the 1870s, there was some talk of a marriage between him and Queen Victoria's youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice. Victoria also reportedly believed that it would be best for "the peace of Europe" if the prince became king of France. The Prince remained a devout Catholic, and retained hopes that the Bonapartist cause might eventually triumph if the secularising Third Republic failed. He supported the tactics of Eugène Rouher over those of Victor, Prince Napoléon, breaking with Victor in 1876.

The Prince remained a devout Catholic, and retained hopes that the Bonapartist cause might eventually triumph if the secularising Third Republic failed. He supported the tactics of Eugène Rouher over those of Victor, Prince Napoléon, breaking with Victor in 1876.With the outbreak of the Zulu War in 1879, the Prince Imperial, with the rank of lieutenant, forced the hand of the British military to allow him to take part in the conflict, despite the objections of Rouher and other Bonapartists.

He was only allowed to go to Africa by special pleading of his mother, the Empress Eugénie, and by intervention of Queen Victoria herself.

He went as an observer, attached to the staff of Frederic Thesiger, 2nd Baron Chelmsford, the commander in South Africa, who was admonished to take care of him.

Louis accompanied Chelmsford on his march into Zululand. Keen to see action, and full of enthusiasm, he was warned by Lieutenant Arthur Brigge, a close friend, "not to do anything rash and to avoid running unnecessary risks. I reminded him of the Empress at home and his party in France."

Chelmsford, mindful of his duty, attached the Prince to staff of Colonel Richard Harrison of the Royal Engineers, where it was felt he could be active but safe. Harrison was responsible for the column's transport and for reconnaissance of the forward route on the way to Ulundi, the Zulu capital.

While he welcomed the presence of Louis, he was told by Chelmsford that the Prince must be accompanied at all times by a strong escort. Lieutenant Jahleel Brenton Carey, a French speaker and British subject from Guernsey, was given particular charge of Louis.

The Prince took part in several reconnaissance missions, though his eagerness for action almost led him into an early ambush, when he exceeded orders in a party led by Colonel Redvers Buller.

Despite this on the evening of 31 May 1879, Harrison agreed to allow Louis to scout in a forward party scheduled to leave in the morning, in the mistaken belief that the path ahead was free of Zulu skirmishers.

On the morning of 1 June, the troop set out, earlier than intended, and without the full escort, largely owing to Louis's impatience. Led by Carey, the scouts rode deeper into Zululand. Without Harrison or Buller present to restrain him, the Prince took command from Carey, even though the latter had seniority.

At noon the troop was halted at a temporarily deserted kraal while Louis and Carey made some sketches of the terrain, and used part of the thatch to make a fire. No lookout was posted. As they were preparing to leave, about 40 Zulus fired upon them and rushed toward them screaming.

The Prince's horse dashed off before he could mount, the Prince clinging to a holster on the saddle — after about a hundred yards a strap broke, and the Prince fell beneath his horse and his right arm was trampled. He leapt up, drawing his revolver with his left hand, and started to run — but the Zulus could run faster.

The Prince was speared in the thigh but pulled the assegai from his wound. As he turned and fired on his pursuers, another assegai, thrown by a Zulu named Zabanga, struck his left shoulder.

The Prince tried to fight on, using the assegai he had pulled from his leg, but, weakened by his wounds, he sank to the ground and was overwhelmed; when recovered, his body had eighteen assegai wounds and had been stabbed through the right eye which had burst it, and penetrated his brain.

Two of his escort had been killed and another was missing. Lt. Carey and the four men remaining came together about fifty yards from where the Prince made his final stand — but did not fire at the Zulus

Carey led his men back to camp, where he was greeted warmly for the last time in his career: after a court of inquiry, a court martial, intervention by the Empress Eugénie and Queen Victoria, he was to return to his regiment a pariah, shunned by his fellow officers for not standing and fighting.

Carey endured several years of social and regimental opprobrium before his death in Bombay, India, on 22 February 1883.

Louis Napoleon's death caused an international sensation. Rumours spread in France that the prince had been intentionally "disposed of" by the British. Alternatively, the French republicans or the Freemasons were blamed.

In one account Queen Victoria was accused of arranging the whole thing, a theory that was later dramatised by Maurice Rostand in his play Napoleon IV.

The Zulus later claimed that they would not have killed him if they had known who he was. Langalabalele, his chief assailant, met his death in July at the Battle of Ulundi.

Eugénie was later to make a pilgrimage to Sobuza's kraal, where her son died. The Prince, who had begged to be allowed to go to war (taking the sword carried by the first Napoleon at Austerlitz with him) and who had worried his commanders by his dash and daring, was described by Garnet Wolseley as "a plucky young man, and he died a soldier's death. What on earth could he have done better?".

His badly decomposed body was brought back to England on board the British troopship HMS Orontes and buried in Chislehurst

|

Later, it was transferred to a special mausoleum constructed by his mother as the Imperial Crypt at Saint Michael's Abbey, Farnborough, Hampshire, England, next to his father.

As his heir the Prince Imperial appointed Prince Napoléon Victor Bonaparte, thus omitting the genealogically senior heir, Victor's father, Prince Napoléon.

It was Chelmsford who was "to take of him". That didn't happen.

*******************************************************************************

*******************************************************************************

Trying to Avenge his position - more orders ignored

. On 28 June 1879 Chelmsford’s column was a mere 17 miles away from Ulundi and had established the supply depots of 'Fort Newdigate', 'Fort Napoleon' and 'Port Durnford' when Sir Garnet Wolseley arrived in Cape Town. Wolseley had cabled Chelmsford ordering him not to undertake any serious actions on the 23rd but the message was only received through a galloper on this day.

Chelmsford had no intention of letting Wolseley stop him from making a last effort to restore his reputation and did not reply. A second message was sent on 30 June reading:

"Concentrate your force immediately and keep it concentrated. Undertake no serious operations with detached bodies of troops. Acknowledge receipt of this message at once and flash back your latest moves. I am astonished at not hearing from you"

On the same day the first cable was received, Cetshwayo’s representatives again appeared. A previous reply to Chelmsford’s demands had apparently not reached the British force, but now these envoys bore some of what the British commander had demanded – oxen, a promise of guns and a gift of elephant tusks.

The peace was rejected as the terms had not been fully met and Chelmsford turned the envoys away without accepting the elephant tusks and informed them that the advance would only be delayed one day to allow the Zulus to surrender one regiment of their army.

The redcoats were now visible from the Royal Kraal and a dismayed Cetshwayo was desperate to end the hostilities. With the invading enemy in sight, he knew no Zulu regiment would surrender so Cetshwayo sent a further hundred white oxen from his own herd along with Prince Napoleon’s sword, which the Zulu had taken 1 June 1879 in the skirmish in which the Prince had been killed.

The Zulu umCijo regiment, guarding the approaches to the White Umfolozi River where the British were camped, refused to let the oxen pass, deeming it a useless gesture, saying as it was impossible to meet all Chelmsford's demands - fighting was inevitable. The irate telegram from Wolseley issued on 30 June now reached Chelmsford, and with only five miles between him and a redemptive victory, it was ignored.

After half an hour of concentrated fire from the artillery, the Gatling Guns and thousands of British rifles, Zulu military power was broken. British casualties were ten killed and eighty-seven wounded, while nearly five hundred Zulu dead were counted around the square; another 1,000 or more were wounded. Chelmsford ordered the Royal Kraal of Ulundi to be burnt – the capital of Zululand burned for days.

Chelmsford turned over command to Wolseley on 15 July at the fort at St. Paul's, leaving for home on the 17th. Chelmsford had partially salvaged his reputation and received a Knight Grand Cross of Bath, largely because of Ulundi; however, he was severely criticized by the Horse Guards investigation and he would never serve in the field again.

But that wasn't the end of Chelmsford.

*********************************************************************************

The Victorian public was dumbstruck by the news that 'spear-wielding savages' had defeated the well equipped British Army. The hunt was on for a scapegoat, and Chelmsford was the obvious candidate. But he had powerful supporters.

On 12 March 1879 Disraeli told Queen Victoria that his 'whole Cabinet had wanted to yield to the clamours of the Press, & Clubs, for the recall of Lord. Chelmsford'. He had, however, 'after great difficulty carried the day'. Disraeli was protecting Chelmsford not because he believed him to be blameless for Isandlwana, but because he was under intense pressure to do so from the Queen.

Meanwhile Lord Chelmsford was urgently burying all the evidence that could be used against him.

He propagated the myth that a shortage of ammunition led to defeat at Isandlwana. He ensured that potential witnesses to his errors were unable to speak out. Even more significantly, he tried to push blame for the defeat onto Colonel Durnford, now dead, claiming that Durnford had disobeyed orders to defend the camp.

Many generals blunder in war, but few go to such lengths to avoid responsibility.

The truth is that no orders were ever given to Durnford to take command. Chelmsford's behaviour, in retrospect, is unforgivable.

Chelmsford had, in any event, another weapon to use against his critics - that of Rorke's Drift.

Though undeniably heroic, the importance of the defence of Rorke's Drift was grossly exaggerated by both the generals and politicians of the period, to diminish the impact of Isandlwana. 'We must not forget,' Disraeli told the House of Lords on 13 February, 'the exhibition of heroic valour by those who have been spared.'

Source wikipedia

My father's father's parents, Philip and Adelaide Durnford, were friends and neighbours of the deposed Napolean III and his wife Eugenie in Chislehurst. My brother has an item of furniture inscribed on the underside by Adelaide as having once belonged to Lucian Bonaparte and given as a gift by Eugenie. The death of the Prince Imperial during the Anglo-Zulu war brought the neighbours closer together. After the subsequent loss of Col. A. W. Durnford, his widow was granted a Grace and Favour apartment in Hampton Court Palace at the request of Queen Victoria. The Queen's concern for the Durnford family went back to my great grandmother having been a goddaughter of William IV's queen, Adelaide, whose name she was given. That link arose because Adelaide's grandfather, Sir John Barton, had been Queen Adelaide's secretary and previously that of the Duke of Clarence before his accession as William IV. Sir John, beside being a noted engineer and inventor, negotiated the Duke's settlement with his mistress Dorothea Jordan, mother of the Duke's many children, before the accession could take place. Sir John was buried, at the new king's request, within St. George's Chapel in Windsor Castle, where a plaque summarises his life. Sir John had been married to the granddaughter of John Harrison, who won the Longitude Prize with the help of George III, and Harrison's descendants then remained in contact with the royal family for longer than a century.

ReplyDelete